|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

NEW WEEK

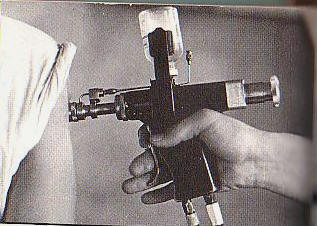

The VA’s Hepatitis C Problem Martin Dames is a highly decorated veteran of the Vietnam War. He received the Bronze Star for heroism in the combat zone and three Purple Hearts for injuries he suffered while fighting. He made it out alive, only to find out years later that those combat wounds got him infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV), a deadly blood-borne pathogen discovered in 1989 that claims about 19,000 lives annually, a large number of them veterans. That number is growing every year. A chronic infection in around 80 percent of cases, HCV often shows no signs of its corrosive presence until extensive liver scarring occurs after decades of infection. In some cases, the disease isn’t found until it has led to cirrhosis—advanced and potentially lethal amounts of scarring. Infection with the virus is a leading cause of liver cancer and transplants in the U.S. Some 3.5 million Americans are infected, including an estimated 234,000 veterans. Approximately 174,000 veterans in government care have been diagnosed with hepatitis C, but an additional 50,000 are thought to carry the infection unbeknownst to them. For treatment, those veterans who know they are sick must go to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and its health care services extension: the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest provider of hepatitis C care in the nation. The VHA serves nearly 9 million patients at over 1,700 sites, but as Dames and many other veterans have found, treatment there is often amiss—especially when it comes to HCV. Bob, another former U.S. Army soldier, also has HCV. (His name has been changed because he fears jeopardizing his VA treatment.) He thinks he contracted it during an accident in childhood that caused his liver to burst, which required an emergency blood transfusion at a local hospital. Bob’s viral infection was discovered by the VA in a routine blood test around 1994, but it took a long time to tell him about it. In 2004, a doctor was looking at Bob’s records on a computer screen. “He asked, ‘What are you doing about your hepatitis infection?’ and I said, ‘I didn’t know I had it,’ and he replied, ‘Oh yeah, we have known about it for 10 years.’” At the time, the only treatment options were the antivirals interferon and ribavirin. Twice, Bob was prescribed a combination therapy of both these drugs and given the maximum dosage, but a debilitating “brain fog” forced him to quit. Had the VA treated him earlier, he has since learned, the outcome might have been much better. The consequences of that delay have been devastating. Advancing liver disease forces him to nap throughout the day, so he can no longer hold a job. And when his legs can no longer carry him, he must crawl up stairs. “They could have and should have done something,” he says. Bob spent the next decade praying for a life-saving organ donation. Getting one isn’t easy, particularly inside the VA, which approves only about 100 a year in a nation that performs over 6,000 liver transplants annually. It’s so bad that at one point a VA physician urged Bob to obtain private insurance so he could try to get a transplant outside the system. Death seemed imminent for Bob until last year, when a VA doctor gave him the “good news”: He had liver cancer. That put him on the fast track for a liver transplant operation. He’s still waiting. In the meanwhile, he’s developed a ghoulish condition known as a “variceal hemorrhage”—the blood vessels that line his esophagus all the way to his stomach are bulging. The vessels “have come out of my skin,” as he puts it. Driving a car is dangerous because a sudden movement could cause a vessel to rupture—and for Bob to bleed to death. “I really do have a fear of the VA,” says Bob. “One foul-up...this is life or death for me.” There’s some real good news: Last year, he finally joined the small number of veterans who have gotten approval for a class of new wonder drugs, including Sovaldi, Olysio and telaprevir, that came onto the market a few years back. These protease inhibitors, which block the replication of viruses, have cure rates exceeding 85 percent, with none of the serious side effects of their predecessors. They also are much, much more expensive. Although drug companies have sharply reduced the price of these new antivirals for the VA, they still cost four times more than interferon and ribavirin: The cost for a 48-week treatment course with the older drugs is between $15,000 and $20,000, according to the VA’s website. By contrast, a 12-week course of treatment with Sovaldi can exceed $50,000 per veteran, or more than $500 per pill. Spending that much on each of the estimated 234,000 veterans with HCV could cost the VA more than $12 billion every year—or about 20 percent of its annual budget. The VHA issued a policy memorandum in September 2011 stipulating that cost should not be a factor in prescribing more effective drugs, but Bob has no doubt the VA has been slow to utilize the new medications because of their striking price tag. He says his treating physician told him of meetings where VA administrators from various departments, including pharmacy, have said, flat out, “‘We are just not going to pay that kind of money.’ They didn’t say they don’t have the money. They said they aren’t going to spend that kind of money on these drugs.” Dr. David Ross, director of the VA’s hepatitis C program, strenuously denies that. “Historically, treatment rate has been low for two reasons,” he says. “One, standard treatments have been awful. The drugs are horrible and don’t work that well. Secondly, a lot of patients have conditions such as depression or substance abuse problems that get in the way of treatment.” According to Ross, some 50,000 veterans infected with hepatitis C have been treated and 15,000 cured since 1999. In addition, since the beginning of 2013, more than 14,000 patients have been treated with the new class of antivirals. Close to 700 veterans are going on the new antiviral medications every week, he says. The increased use of the new antivirals shows in the budget: Between 2011 and 2013, the VA spent an estimated $100 million on medications. For fiscal year 2015, Ross says, the VA has allocated $696 million for new HCV drugs (17 percent of the VA’s total pharmacy budget). Ross also stresses that he recommends treating HCV as early as possible. However, a recent VA memo recommends urgently treating those with advanced liver disease but holding off for patients with mild cases of the illness. Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states clearly that “the longer people live with hepatitis C the more likely they are to develop life-threatening liver disease.” That’s a view a view shared by Dr. Bennet Cecil III, who worked as a gastroenterologist at the Louisville VA Medical Center, in Kentucky, for 16 years before retiring last year. Cecil has for years been sparring with Ross over what he considers to be the VA’s “lack of enthusiasm” for handling the crisis. He claims that at the VA medical center where he worked, denying treatment for budgetary reasons was not official policy but he saw it happen all too often. “The problem has been the cost of treatment,” Cecil says. “The VA is a bureaucracy, and bureaucrats have to guard their budgets. They get so much money each year, and that money has to last. Since treatment has been expensive, they have slow-walked it. For example, the Louisville VA strictly limited his use of telaprevir and boceprevir, two antivirals that came out in 2011. Meanwhile, he was free to prescribe as much interferon and ribavirin as he liked. The former were much more effective—and expensive—than the latter. The VA would also “redirect” his patients to doctors who weren’t so gung-ho about prescribing the costlier medication, Cecil says, and would tell veterans “they did not need treatment. People were given vitamins and zinc instead of interferon.” (Bob laughed when he heard this—he still routinely gets free zinc in the mail from the VA. He throws it out.) Speaking on behalf of her ailing husband, Dorothy Dames says VA physicians knew Martin Dames had life-threatening cirrhosis as early as 2002, but didn’t tell them for more than eight years. As with Bob, the late notification led to horrendous consequences for Dames’s health. He was eventually treated with interferon-based therapy and ribavirin, but by 2010 his cirrhosis had advanced to liver cancer and he was in desperate need of a transplant. A VA doctor declined to put him on a waiting list, saying the poor health of his lungs disqualified him. “They don’t treat you, and then they wait for you to get very sick, and then they say you’re too sick for a liver transplant,” Martin Dames says. He’d be dead today but for the efforts of his wife, who mobilized the support of others in their “very patriotic town” in Missouri and enlisted help from their congresswoman, Jo Ann Emerson, whose staff made several phone calls to the VA. Three months later, Dames finally got his liver transplant, but his ordeal was far from over. Though the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and other health foundations recommend treating with antiviral drugs before or immediately after a liver transplant, Dames’s VA doctor did not. And when Dames asked about getting meds, “sit and wait” was the VA’s response. The VA doctor told Dames to wait for more effective drugs to arrive—and in the meanwhile they’d monitor his viral levels. So Dames waited. And then the virus “came back with a vengeance,” his wife says. By the time the new antivirals were approved last November, Dames was on his deathbed. He says the hepatitis C virus hasn’t just ruined his liver. His viral load had risen to the point where it was wreaking havoc on his kidneys. Though the new antivirals have cleared up his hepatitis C, it’s too late for his kidneys. Dames is now facing a grim reality: dialysis or die. His wife says, “He can’t live without dialysis,” treatment where waste and unneeded water are removed from the blood using artificial means, typically utilized when a person’s kidneys fail. “He has 30 pounds of fluid in him, his blood pressure is high, and his heart is beating irregular. If they don’t remove the fluid, he can’t breathe.” If Dames does succumb to the illness, it will, sadly, not be a unique tragedy. Cecil estimates that as many veterans of the Vietnam War will die from hepatitis C infection as were killed in combat. Eleven percent of the veterans of that war are infected, he says, and many are not receiving the treatment they need. Nevertheless, the experience of trying to understand and address HCV was not something that Dames and his wife, as well as other veterans’ families, ever would have predicted, and this has changed their view of the VA. “We trusted the VA until 2009, when they knew he was sick but didn’t do anything,” says Dorothy. “Now we watch them like a hawk.” |

|

|

|

|