PRISON

DRUG & PLASMA PROJECTS LEAVE FATAL TRAIL

PRISON DRUG & PLASMA PROJECTS LEAVE FATAL TRAIL

The New York Times, Page 1

July 29, 1969

By WALTER RUGABER

Washington, July 28 --

The Federal Government has watched without interference while many people sickened and some died in an extended series of drug tests and blood plasma projects. The profits generated by these activities have gone to an enterprising contractor for the nation's biggest pharmaceutical manufacturers. The immediate damage has been done in the penitentiary systems of three states. Hundreds of inmates in voluntary programs have been stricken with illness and serious disease. An undetermined number of the victims have died.

In a broader sense, countless millions of American consumers have been involved. Potentially fatal new compounds have been tested on prisoners with little or no direct medical observation of the results. Prisoners failed to swallow pills, failed to report serious reactions to those they did swallow, and failed to receive careful laboratory tests. These studies have generated data that have in turn been used to justify the sale of drugs at prescription counters across the country.

This forbidding trail has been marked out by an Oklahoma-born physician named Austin R. Stough and corporations in which he owns a substantial interest. Despite his importance in two vital fields, he is practically unregulated in either.

As a general practitioner who reports no formal training or education in pharmacology, he is said to have conducted between 25 per cent and 50 per cent of the initial drug tests in the United States.

The 59-year old doctor, whose companies have been blamed for the repeated use of dangerous methods and inadequate equipment, is estimated to have produced the plasma for about a fourth of an important byproduct that is widely used to protect people exposed to infectious diseases.

These prison-based enterprises have regularly incurred local disfavor. Dr. Stough was evicted from one prison by the Oklahoma authorities in 1964. He was forced out of an Arkansas prison by officials there in 1967. One of his corporations is now under orders to close down prison operations in Alabama.

But Dr. Stough (rhymes with HOW) is said to retain financial interests in some private blood banks in Birmingham and Dallas, and he is known to be seeking connections with prison systems in new areas.

He can do so freely. He has incurred no penalties, and dissatisfaction with his performance in one state has not prevented a repetition of it in another.

The Federal Government and the pharmaceutical industry - the two forces with enough broad power to compel safe practices from state to state --- have maintained a general indifference at every turn.

Several agencies within the Department of Health, Education and Welfare have known the details of Dr. Stough's plasma collections and drug tests for years. They have not curtailed them.

Some officials in Washington have attributed their inaction to gaps in the law and in the regulations under which they work, and a shortage of specific Federal standards is occasionally apparent.

But critics in Congress and elsewhere have blamed bureaucratic inertia and timidity for the failure to regulate drug and plasma operations, and a lapse in enforcement is also occasionally apparent.

For example, the Food and Drug Administration employs only a single physician to conduct field investigations of all the studies under way in the United States, and the agency's inquiries rarely go behind the dry scientific data.

Methods Called Dangerous The Division of Biologics Standards, a unit of the National Institutes of Health that is responsible for the regulation of blood products, recently asserted that the safety of plasma donors was not its concern.

Several major pharmaceutical manufacturers have recognized that some of the methods employed by Dr. Stough were extremely dangerous. They continued to support him with large sums of money.

An executive of Cutter Laboratories once acknowledged, for instance, that gross contamination was apparent in the areas where the largest blood plasma operations were conducted. The rooms were "sloppy," he observed.

When a Government doctor asked why Cutter continued to reward such an enterprise with hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of business, the executive explained that the Stough group enjoyed crucial "contacts" with well placed officials.

Fees and Partners These contacts involved, among other things, the payment of sizable retainers to influential lawyer-legislators and the establishment of "partnerships" for a number of prison physicians who remained on the public payrolls.

With neither Government nor industry intruding, with most of their records held in secret, with officials passing the problem on to someone else, Dr. Stough prospered at his work throughout the nineteen-sixties.

He has generally declined to talk with local newspapermen about the controversies involving him. And he recently refused to grant an interview with a reporter for The Times, "We've taken the position of no comment," Dr. Stough said during a recent telephone conversation with a reporter who had asked to see him. "I don't think we're interested in airing anything in the newspaper." "We think some people have made a mistake," he remarked, referring to the medical observers, editorial writers and state officials who have assailed him. But, he added, "I'm not looking for revenge on anybody."

Efforts to photograph Dr. Stough were unsuccessful, and an extensive search of newspaper files and other sources turned up no pictures of the physician.

Started in Oklahoma Dr. Stough graduated from the University of Tennessee Medical College, spent a one-year internship in Oklahoma City, and opened a private practice in McAlester, site of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, late in 1937.

He soon began to serve, on a part-time basis, as the prison physician. With direct access to more than 2,000 inmates, his drug tests began to grow extensively. In the meantime, he started a new endeavor.

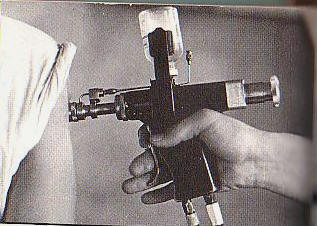

On March 25, 1962, the inmates at McAlester began lining up to participate in a medical procedure called

plasmapheresis. Under it, a unit of whole blood is drawn and the plasma, a fluid that makes up about 55 percent of the blood, is taken out.

The remaining cells are reinjected. That was the critical step on Sept. 19, 1962, when one of Dr. Stough's technicians processed an inmate named Tommy Lee Knott, 47, an illiterate prisoner with a long criminal record.

Knott's blood type was O-positive, but he subsequently charged in a lawsuit that after the plasma had been drawn off, the technician pumped another man's cells, which happened to be A-negative, back into his veins.

Organs Damaged Unfortunately for Knott, his liver, lungs, brain, kidneys and other organs were injured, his nervous system underwent shock, and his weight dropped 58 pounds in 17 days.

In suing Dr. Stough and two associates for $270,000 in damages, Knott also reported that the incompatible blood had caused a double hernia, permanent secondary anemia and a 10 per cent reduction in life expectancy.

The defendants managed to settle out of court for $2,000 after Knott, who had been removed from the penitentiary for treatment, went off on a crime spree that landed him in a small town jail.

Only three months after this inauspicious episode, Dr. Stough embarked on an ambitious expansion effort. The financial rewards inherent in his initial plasmapheresis program would now be greatly multiplied.

He brought his plasma operation to Kilby prison, a drab institution near Montgomery, Ala., in December, 1962, and in the following year he began drawing blood in two more of the state's prisons, Draper and Atmore.

In October, 1963, he started a plasma program at the Cummins Farm, a sprawling unit of the Arkansas state penitentiary that was quietly going through an era of general brutality and neglect.

Proteins Extracted Plasma itself can be used in the treatment of shock, but it also contains a number of proteins, including gamma globulin, that can be extracted and employed to counteract a variety of medical difficulties. The gamma globulin from most donors contains enough antibodies against such diseases as measles and hepatitis to be effective when it is reinjected into a person who has been exposed to those diseases. This is not the case, however, with diseases such as mumps, whooping cough, tetanus and smallpox. Groups of donors receive vaccinations to build up the antibodies in the gamma globulin intended to treat these illnesses. The result is known as hyperimmune gamma globulin, and much of the plasma Dr. Stough extracted was used by manufacturers to produce this serum. It can be a hazardous process.

Dr. Stough demonstrated this immediately upon his arrival in Arkansas. Andrew Buddy Crawford, a 45-year-old inmate at the Cummins Farm, received the first in a series of whooping cough shots on Nov. 23, 1963.

Died After 8th Shot More amounts of the vaccine were injected weekly for a time, and on March 7, 1964, after a two-month lapse, Crawford received his eighth shot. He became ill about a week afterward. Crawford died slowly and in very painful fashion, and three Little Rock physicians, who reported the process with the lack of patients' names often encountered in medical journals, said it was probably the result of the repeated vaccinations

It was left to The Pine Bluff (Ark.) Commercial to report only last January, that the man who died on June 13, 1964, was Andrew Buddy Crawford, and that the program involved was directed by Austin R.

Stough.

As a measure of his grip on the market at about this time, a Government source calculated that Dr. Stough's plasma would produce 193,970 cubic centimeters of hyperimmune gamma globulin solution monthly. Since only about 800,000 cubic centimeters of this type of plasma product were distributed each month throughout the United States, Dr. Stough's output was the source of practically a fourth of the entire national supply.

Other Prisons Eyed "With demand exceeding supply," a Government doctor wrote of the boom, "inquiries were made in other states concerning the possibility of opening plasmapheresis centers in other . . . prisons."

A certain style had developed. In Oklahoma, Dr. Stough himself was the prison physician. The salary of $13,200 a year was inconsequential by his standards, but the standing it gave him within the prison was invaluable. So, in Alabama, he awarded Dr. Irl R. Long, the senior prison physician, a financial interest in the program. Until a few weeks ago, Dr. Long simultaneously received a salary of $942 a month from the state.

A committee of the Alabama Medical Association remarked in a report issued earlier this year that "this unconscionable situation, regardless of reason, should never have been permitted to come into existence."

The prison physician in Arkansas, Dr. Gwyn Atnip, was paid $20,000 a year for his work in the plasma program there. As a desperately needed doctor among the inmates, he received $8,000 annually from the state.

Got Political Aid Dr. Stough also lined up political support outside the prisons, a tactic that demonstrated its importance when members of the Oklahoma Legislature began to ask whether his penitentiary operations were sanctioned by law. One of Dr. Stough's most vehement opponents was Gene

Stipe, then a State Senator. But early in 1963 Senator Stipe changed sides and successfully pushed a bill that firmly established the physician's standing in the prison.

Later it was discovered that at about the time this change of direction occurred and the saving law was enacted, Mr.

Stipe, a lawyer, began to receive a $1,000-a-month retainer from the concern headed by Dr.

Stough.

A spokesman for the organization asserted that the money was for legal services only. Mr. Stipe agreed. Henry

Bellmon, then Governor, expressed displeasure but noted that the state had no applicable conflict-of-interest law.

The political nature of the matter was usually most apparent when Dr. Stough moved to enter the penitentiary system in a new state. His drive on the major prison at Reidsville, Ga., was an example of the technique.

Checked With Center Dr. Joseph Arrendale, the institution's medical director, one day telephoned Dr. Ronald F. Johnson, then on the staff of the National Communicable Disease Center in Atlanta.

Dr. Johnson had followed Dr. Stough's plasmapheresis operations for some time, and Dr. Arrendale wanted advice. In a memorandum of the conversation, Dr. Johnson reported as follows:

"It was clear that Dr. Arrendale did not favor [a plasma program]. However, he felt that Dr. Stough might be 'bringing political pressures to bear through the state legislature' which could clear the way for such a program."

The Georgia campaign ultimately failed, and a similar move on the state prison at

Parchman, Miss., was also turned back. But by then Dr. Stough had encountered serious difficulties in his existing programs.

The five prisons in which he was operating by the end of 1963 all were drastically in need of operating funds, and all exhibited obvious signs of longstanding general neglect.

No Records The factors pertinent to Dr. Stough's activities included a lack of medical attention (it bordered on the nonexistent in Arkansas), an absence of records, and an atmosphere of isolation and secrecy.

Still, Dr. Stough's trail remains vivid at each significant turn, and its progress behind the high walls of Kilby Prison serves to illustrate the type of infection that was spread through four other institutions. By April, 1963, five months after Dr. Stough had opened his plasmapheresis center at

Kilby, the incidence of viral hepatitis an often fatal disease of the liver, was climbing sharply.

From none or one or two cases a month, the disease now rose to more than 20 in a single period. Moreover, the outbreaks held generally firm between 10 and 15 a month through the following November. The rates then soared again. There were 29 cases in December, 22 in January, 1964, 23 in February, 27 in March, and 27 in April. A tenth of the prison population had been admitted to the Kilby hospital.

Joe Willie Tifton, 46, died on March 18. Emzie B. Hasty, 42, died on April 14. Charlie C. Chandler Jr., 31, died on April 16. David McCloud, 27, died on May 22. Each death was attributed to infectious hepatitis.

Little bits and pieces then began to leak to the outside world. A penciled note from one inmate said, "They're dropping like flies out here." But a prison spokesman said:

"The doctors are quite confident that there is no connection between the plasma program and the cause of hepatitis and jaundice."

Dr. Stough's partner, Dr. Long, spoke as the senior prison physician. "That same program is being carried on at Draper and Atmore," he declared, "and there have been no cases reported there." This assurance was published in The Montgomery Advertiser on May 24.

Inmates Afflicted Actually, the records show that by the end of May, at the time he spoke, 37 inmates had been hospitalized at Atmore and six sent to the infirmary at Draper, all with the same symptoms. Dr. Ira Myers, the state's public health officer, told the National Communicable Disease Center as late as June 5 that an epidemic "apparently" was under way in the prisons. There was, he said, "no direct confirmation."

The exact number of hepatitis cases in the five prisons was never established and is never likely to be. Too many medical histories vanished, too many were never completed, and too many were improperly kept by "inmate doctors."

Some 544 cases were firmly established, and that conservative figure is the one most often used. But the communicable disease center records also contain estimates of more than 800 and evidence that the figure could run to more than 1,000.

The number of deaths is similarly undetermined. In addition to at least the four in Alabama, there were reports of at least one in Arkansas and at least one in Oklahoma.

The dimensions of the disease were more clearly and precisely stated in sets of percentages, or "attack rates," that measured the incidence of hepatitis among those who gave plasma and those who did not.

At Kilby, for example, 28 per cent of the men who participated in Dr. Stough's program came down with the disease. For those who did not take part, the rate was only 1 percent.

The rate for participants in one of the barracks at Kilby was 39.1 per cent. At the four other centers, the illness struck between 20 per cent and 26 per cent of the donors and from 0.9 per cent to 1.8 per cent of the

nondonors.

First Allied to Jaundice The Federal investigators, reflecting scientific caution, initially referred to the prison cases as "illnesses associated with jaundice." A number of their records employed this phrase. Jaundice means a yellowish skin, and while it is a symptom of hepatitis its presence is not conclusive. After extensive testing and study, however, the Government doctors concluded:

"The illnesses seen in these prisons seemed to be indistinguishable with viral hepatitis. It is not felt that any serious question of the nature of the illnesses need be entertained." Hepatitis is a threat in every blood and plasma program, but the careful use of properly designed equipment can reduce the danger virtually to zero. Dr. Stough managed a double play: technique and apparatus both were cited in the epidemics.

The details are complicated, but the general picture drawn by the experts was reflected by K. T. Kimball, an executive of Fenwal Laboratories who had observed some of the plasma operations and who reported to Dr. Johnson of the Atlanta center, according to a written memorandum, as follows:

"Mr. Kimball directed the conversation to the general level of care exercised by Dr. Stough's technicians. He felt that collection of large amounts of plasma in a rapid operation using equipment of simpler design that Dr. Stough approved might easily lend itself to a high level of contamination of technicians' hands and surfaces of tables, equipment, and the actual bags and tubing used in the procedure.

"He felt that contamination of these objects by the plasma of all donors could have occurred, and that absence of strict medical supervision could easily have led to short cuts in and inadequacies of sterile technique."

This was equally apparent to Byron Emery, an official of Cutter Laboratories who also visited some of Dr. Stough's operations and who also talked with Dr. Johnson. Another Federal memorandum reported:

"Mr. Emery stated that when he visited Alabama in April, 1964, he was 'appalled at the situation' he found. He said the plasmapheresis rooms were 'sloppy' and that gross contamination of the rooms with donors' plasma was evident.

"Mr. Emery stated that [Dr. Stough and an associate] . . . could not be trusted to carefully supervise such a plasmapheresis program.

"I then asked Mr. Emery why Cutter did not choose to operate such plasmapheresis programs by themselves without using Dr. Stough's group as an intermediate company . . .

"Mr. Emery replied that Dr. Stough had contacts at the prison and it was through him the permission was obtained from the prison officials to operate the program."

Remained Big Customer Cutter nevertheless remained one of Dr. Stough's biggest customers.

Alabama shut down the plasmapheresis centers in the middle of the epidemics and blocked Dr. Stough's efforts to start them up again. Oklahoma had taken over the plasma and drug-testing programs almost simultaneously just before the Federal investigation.

In Arkansas, where he had never tested drugs, Dr. Stough was permitted to continue his plasma operations for three years before a quasi-public foundation successfully replaced him.

And although the Alabama authorities had stopped the traffic in plasma, they permitted him to continue his drug tests without interruption. The enterprise was quickly stepped up. A pharmaceutical manufacturer generally develops a new product in the laboratory, tests it on animals, and then notifies the Food and Drug Administration that a three-phase tryout on human beings is ready to begin.

Phase one is in many ways the most delicate step of the three because it is designed to establish basic factors such as toxicity, safe-dosage rates, metabolism, absorption, and elimination. Because of their critical nature, the first-phase tests are usually carried out on healthy subjects. The drug is tried on people who suffer from the target disease only after the phase one hurdle is cleared. Phase two involves limited administration of the drug to "carefully supervised patients," and phase three embraces "extensive clinical trials" that can include studies by doctors in private practice.

Company Judges Doctor The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for monitoring the date and for approving the advance from phase to phase. The role of the individual manufacturer is substantial, however. It is basically the company, for example, that judges a doctor's qualifications as a drug investigator, chooses him to do the job, directs the testing, assembles the results and pays the fee.

Healthy prisoners who by definition exist in closely controlled circumstances are perfect for phase one studies, and Dr. Stough remained in heavy demand by pharmaceutical concerns. The Food and Drug Administration, citing regulations of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, refused requests by The Times to examine its records on Dr.

Stough. A spokesman for the agency said, however, that since 1963 the physician has carried out some 130 investigational studies for 37 drug companies. Other types of tests and work by an associate involved 45 additional programs.

The F.D.A. declined to disclose the names of the drugs that Dr. Stough examined or the names of the companies for which he worked. Some of the information has been obtained from other sources, however.

Big Companies The companies included the Wyeth Laboratories Division of American Home Products Corporation; the Lederle Laboratories Division of American Cyanamid Company; the Bristol-Myers Company; the E. R. Squibb & Sons Division of Squibb Beech-Nut Inc.; the Merck, Sharp & Dohme Division of Merck & Co. and the Upjohn Company. These concerns, according to the current directory published by Fortune Magazine, are among the 300 largest corporations in the United States.

An investigation of Dr. Stough's work for these and other concerns began earlier this year after Harold E. Martin, editor and publisher of The Montgomery Advertiser, wrote a series of highly critical stories about the drug studies. The State Board of Corrections asked the Alabama Medical Association to name a committee of inquiry, and Dr. Tinsley R. Harrison of Birmingham, a nationally known cardiologist, was selected as chairman.

Even when the committee dealt with the welfare of the inmates its investigation inevitably raised broader issues, for Dr. Stough's "findings" became data and the data helped to justify public sale. The medical association investigators concluded not only that Dr. Stough's work had been "bluntly unacceptable" but also that as one result, "the validity of the drug trials themselves must occasionally be seriously in doubt."

Because of the Food and Drug Administration's refusal to permit an inspection of its files, it is impossible to determine conclusively whether Dr. Stough ever reported unfavorably on the drugs he was paid to test.

However, he has published a number of scientific articles on his findings, and a review of those cited in the comprehensive Cumulated Index Medicus since 1960 discloses not a single critical appraisal. It was learned from independent sources that one of the drugs Dr. Stough had tested was

Indocin, a best-selling product of Merck, Sharp & Dohme that is used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Stough's findings on Indocin are unavailable, but it went on the market after largely favorable data had been generated by company-paid investigators, and the subsequent controversy points up the broad significance of testing.

Indocin was assailed repeatedly in testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Monopoly. Contrary to findings of the initial data, witnesses said, careful tests had found the drug no more effective than aspirin, and it produced serious effects as well. A careful medical examination in advance of a drug test is regarded as essential to insure that the prisoners involved do not show signs of subtle disabilities that would make the study invalid. A member of Dr. Harrison's committee recalled during an interview that one day he and another investigator turned up at Kilby Prison to discover that 80 inmates had been examined for a new program in just four hours.

Since that meant an examination every three minutes, the investigators asked to see the records. None were found on the premises - not for a single prisoner. The records that existed were said to be at Dr. Stough's headquarters. The committee noted in its report that prisoners about to embark on a new test had "received a rapid explanation of the purpose" that left "considerable variation in the understanding of what had been said."

No Doctor Present The committee continued: "All this had seemingly been done by technicians with no physician being present as far as could be determined. Two of the four prisoners who were interviewed indicated that they had never been examined by a physician while they were in the prison although they had been on several drug trials."

The fundamental purpose of a drug test is to spot any adverse effect and report it. There were breakdowns in Dr. Stough's operation, and Dr. Harrison's committee cited a number of examples. First, it encountered a Mr. Howell, "a man with very little previous medical training whose experience before entering his present position had been that of a venereal disease inspector."

"It was stated with pride by this individual, who functions as hospital director, that he himself was able to deal with nine out of every 10 patients who came to him so that the doctor was not bothered." A number of qualified medical sources said that that without a physician regularly on hand to look over the inmates who took drugs, it would have been "totally impossible" to gauge reactions.

Prisoner Fees Varied Dr. Harrison's committee took up the question of fees paid by Dr. Stough to inmates who participated in drug tests. These varied widely, but a man could usually make at least $1 a day for taking a series of pills.

This was big money for people who otherwise received only 50 cents every three weeks for incidental spending, and it created what one investigator called "a built-in negative feedback."

Prisoners often covered up severe reactions in order to keep on with the tests, and several told The Montgomery Advertiser that they shammed taking pills and later spit them out. The medical group said of one inmate:

"He had hung on to the end [of a test] although he had been feeling very ill and had not complained of this illness because it would have meant his losing the pay which he was hoping to receive for his participation."

One conscientious experimenter who has gone deeply into the question of fees believes that that a prospective subject should be offered no more than two or three times the amount he would receive without taking part.

Nurember Code Cited The medical investigators underlined the importance of the fees and inadequate explanations of the tests by attaching to their report the Nuremberg Code, developed after the concentration camp excesses of Nazi doctors.

The code calls for "free power of choice" and holds that a subject "should have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the elements of the subject matter involved as to enable him to make an understanding and enlightened decision." The Alabama committee also inspected Dr. Stough's laboratory. Its role in analysis samples taken from the inmates was especially important since the direct medical observation was rated low. In one instance the group found an error of about 40 per cent in the control agent against which laboratory samples from about 20 prisoners were being measured. The investigators said:

"This was pointed out to the laboratory director and he excused it [on grounds that the committee rejected]. His attitude to us was unacceptable and reflected poor technique."

The operation "probably compares favorably with many small hospital laboratories in Alabama," the group concluded. But it "lacks the better qualified personnel and more careful quality control seen in better run laboratories."

Only One Physician The committee reported that on top of the other problems, both Dr. Stough and Dr. Long had "limited training in basic pharmacology." The available biographical information shows they had no formal education in the field at all.

"You might say they have had a lot of on-the-job training and background," one clinical pharmacologist said. "But this is a weak argument. Nowadays, with the sophistication of modern drugs, you need more than this." Last May, after the State Board of Corrections had a look at the committee's report, Dr. Stough received another eviction notice and started to close down the drug studies in Alabama.

Thus, Dr. Stough suffered another setback. As before, a state saved its prisons from any further trouble. But as usual, the Federal authorities and the pharmaceutical companies remained silent. The single physician employed by the Food and Drug Administration to investigate drugs tests throughout the United States has visited Dr. Stough's operations twice, an agency spokesman said.

Some citizens tend to think of the agency as an eternally vigilant organization, and in his dealings with local officials and newspapermen Dr. Stough has turned this misapprehension to advantage.

"They [F.D.A. officials] love to close people down," he said in the brief telephone conversation in which he refused to grant an interview. "So if I was off-color, they'd be on me like a hawk." "That's one of the reasons the [Alabama Corrections] Board wasn't concerned," explained Frank Lee, the state's commissioner. "We knew they

[F.D.A. officials] came in here and looked into the operation."

Dr. Herbert L. Ley Jr., the F.D.A. Commissioner, branded Dr. Stough's assertion "a non sequitur." The Food and Drug Administration's lone medical inspector is alert to "flagrant" dishonesty, and there have been men who tested drugs on nonexistent people and who produced imaginary results.

But an inspection is limited mostly to checking data that have been submitted to the sponsoring drug company to insure that it agrees with data sent to the agency. There is little or no effort to look behind the figures. "Our responsibility is not the direct supervision of the [drug] investigators," Dr. Ley said in an interview. "Our responsibility is to evaluate the data that come in to us. We can't be omnipotent or omniscient."

While the agency has never found occasion to reprimand Dr. Stough, its inspector, Dr. Alan B.

Lisook, did make some "suggestions" earlier this year about "the lack of medical supervision of patients."

Not Enough Supervision "We told him we thought there should be more supervision," Dr. Lisook said, "and he admitted there was not as much as he would like because of the volume of drugs being tested." This was virtually an acknowledgment by Dr. Stough that more tests had been undertaken than could be adequately overseen, but the

F.D.A. did not require change.

The agency "frowns" on insufficient supervision, Dr. Ley said, but under present policies there are no specific minimum standards. In the tray area that results, frowning is about the limit. Since between 25 per cent and 50 per cent of the phase one studies have been concentrated in Dr. Stough's hands, Dr. Ley was asked whether volume alone - quality aside - concerned his agency.

"It's a red flag, there's no question about that," he replied. But the commissioner explained that neither law nor regulation permitted the agency to force a cutback in the number of studies assigned to a single man. There is no step short of outright disqualification for obvious misconduct, Dr. Ley said. That is an action the

F.D.A. has taken no more than a dozen times in its history.

Shortage Charged The drug companies contend there is a shortage of investigators, and Dr. Ley said that while he believed there were enough to study the "really new drugs," he wanted to avoid charges that the agency blocked progress.

"It's harder to get a driver's license in the United States than it is to get fatal drugs," complained Dr. William M. O'Brien, an associate professor of preventive and internal medicine at the University of Virginia. He added: "To get a driver's license you have to take tests, show you know how to drive, and so on. For drugs, you just walk in the door and say, "I'm an M.D. I want to test drugs.' It's fantastic. It's unbelievable."

It is difficult to measure the precise sums of money that the pharmaceutical industry has poured into Dr. Stough's operations, but a number of reliable clues are available.Operating within at least nine separate corporations, the major one of which is Southern Food and Drug Research, Inc., Dr. Stough has a gross income in a good year probably approaching $1-million.

He has not carried a high overhead. His net income in Alabama in 1967 was nearly $300,000 (on a $500,000 gross), and his profit before taxes in Arkansas in 1966 was about $150,000. The Alabama Medical Association's committee treated the drug manufacturers with circumspection in its report, suggesting that the companies could hardly police the state's prisons.

But it pointed out that the makers, as well as the Food and Drug Administration, had engaged in monitoring of the drug tests that might have been "too superficial and too remote to provide maximum safety." The committee also found that in sponsoring Dr. Stough's tests the drug concerns had given "tacit approval" to his research. In this, it reported, the companies had "demonstrated some lack of discretion."

"Our companies are usually pretty careful about who they have doing phase one work," said J. C. Joseph

Stetler, president of the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. "They aren't interested in guys who aren't doing a first-class job." Mr. Stetler said that some concerns might make more rigorous over-all studies of potential investigations than others and that in some instances the day-to-day supervision "gets to be seemingly routine."

Heavy demand for phase one work may also be a factor in quality, Mr. Stetler added. But he said he was not sure the Government should restrict an investigator's work for high volume if the "end product" was satisfactory.

Each of the pharmaceutical companies that could be identified as having retained Dr. Stough was asked to comment on his drug testing, and each defended the validity of the data he submitted. For example, Merck, Sharp & Dohme said in a prepared statement that Dr. Stough's "facilities, staff, volunteer group, and prior experience were particularly suited" for the studies it required.

The physician has conducted 14 projects for the concern since January, 1968, and, the company's statement concluded, "in our opinion the studies were properly conducted and the data provided have been sound." Merck, Sharp & Dohme asserted that practically all of the studies carried out by Dr. Stough had been "extensively studied and clinically used" by others and that some of the drugs had already been approved for marketing.

Lack of Criticism A spokesman for Lederle Laboratories pointed out that Dr. Stough's testing operations at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary had not been criticized publicly by qualified medical observers. Wyeth Laboratories said it had retained Dr. Stough for only a single study. The company said he was hired in 1964 to test an experimental drug that was never placed on the market and had not been used since. One company official, who asked not to be identified, remarked: "How he [Dr.

Stough] operated, how he had his machinery set up - they didn't even know at the prisons."

To ship blood products in interstate commerce requires a license from the Division of Biologics Standards, and when a manufacturer obtains one he must face and continue to face regular inspections.

Dr. Stough does not have and never has had a license from the division. Under the so-called "short supply provision" of the agency's regulations, a licensed company can pick up the scarce plasma at Dr. Stough's door and ship it to its laboratories without violation.

Serious things can happen if the slightest thing goes wrong once the plasma reaches the hands of a licensed company. Nothing can happen, so far as the standards division is concerned, if everything goes wrong before that time. Dr. Stough incurred no Federal disfavor for the hepatitis epidemic in three states because the disease apparently was routinely killed out in the manufacturing process that turned his plasma into gamma globulin.

"The conclusion that we came to was that the quality of the product was not affected," recalled Dr. Roderick Murray, the division's director, "and therefore we had no backing to tell them [the companies] not to use plasma that came from

Stough."

Invitation Rejected

This is felt so keenly at the division that Dr. John Ashworth, then an agency official, refused an invitation from Dr. Johnson just to go and look at a plasmapheresis operation. "He said that his appearance at the plasmapheresis center would not be consistent with the policy of

D.B.S.," Dr. Johnson wrote, because the policy did not include "direct supervision or policing of the actual procedures."

"Any time that we've attempted to write into the regulations elements that are designed to protect the donor," Dr. Murray said, "this has been disallowed because there's no statutory authority."

What about the communicable disease center, which traced the hepatitis epidemic directly to Dr. Stough's programs? That agency, a spokesman said, is only a consultant to the states. Enforcement is up to the state authorities.

The question thus is put to the Alabama public health officer, Dr. Myers. He answers that the State Health Department has "no specific jurisdiction in

the prisons."

CUMMING

PRISON

The FDA has suspended plasma production at the Arkansas Department of Correction facility at Grady, where an average of 550 to 600 inmates have been giving plasma since 1967, but now is setting an April 23 deadline for the prison system to seek a hearing on the proposed permanent

revocation.-Overbleeding of inmate donors;

-Using donors previously disqualified because of a history or symptoms of hepatitis, which can be transmitted through plasma;

-Inadequate storage of plasma to prevent contamination; and

-Failure to note on the plasma whether testing had been done for signs of hepatitis and

syphilis.

''FDA found that the establishment has demonstrated continued non-compliance with those requirements designed to assure the safety, purity, identity and quality of plasma, as well as the requirements for donor protection which are intended to assure a healthy donor population and that the significant deviations involved management staff as well as other employees,

-Continued maintenance and use of inaccurate and incomplete records related to the collection, processing and storage of source plasma;

-Instances of intentional and willful disregard for proposed standards;

-Alterations of records and files to conceal violations; and

-Apparent inadequate training and ineffective supervision of the plasma center staff.

FDA officials said statements from current and former staff ''revealed that individuals formerly employed in management positions at the center either had initiated or condoned the destruction or alteration of records concerning these activities and had acted to conceal these deviations from FDA.''

FDA officials said this is the only current suspension against a prison system plasma center.

John Byus, the department's medical director and liaison to the plasma center, said the hepatitis situation was the ''main issue,'' and suggested that the other deviations were cited to help make a case against the center.

''When they talk about revocation or issues of license inspection, they look at a center historically and lump everything together to support a particular direction they want to take,'' he said.

''The key is the wording of FDA's regulations. On overbleeding, for example, that's based on body weight and other things. If you're a milligram off on an inmate's body weight, it's called a violation.''

Byus said the FDA had inspected the center annually since 1967, and that the problems had been discussed openly at meetings of the Board of Correction.

http://www.bloodtrail.com/news/remick.html

Not for commercial use. Solely to be used for the educational purposes

of research and open discussion.

Infusion of real estate adds to

Stough's growth; Stough Enterprises Inc

Monk, Dan

Business Courier Serving Cincinnati - Northern Kentucky

No. 50, Vol. 14; Pg. 19

April 10, 1998

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Plasma company adds properties to holdings

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Most companies take months to complete a site search.

But when Stough Enterprises Inc. entered the Cincinnati market in 1968,

the search lasted only a few minutes. That was just long enough for the

company's founder, Dr. Austin Stough, to find a building for rent on Main

Street in Over-the-Rhine.

A retired general practitioner from Montgomery, Ala., Stough had just

started a blood-plasma center in Birmingham. He wanted to expand to a

second city and chose Cincinnati by serendipity.

"We just kind of went for an afternoon drive and didn't stop," recalls

Stough's son, Michael, who now runs the family business.

Dr. Stough died in 1972, as Michael was studying biology at University of

Cincinnati. The younger Stough took charge of the company in 1975.

Now, 30 years after his father first leased the former Hanke Bros.

department store on Main, Stough is preparing to move his company's

headquarters into that building from its current home at 1110 Main St. He

spent $ 5 million rehabbing the four-story Hanke property at 1128 Main St.

Just a few doors south of the Hanke building is Ohio Blood Plasma Inc.,

one of seven plasma centers now owned by Stough Enterprises.

Plasma remains the core of the Stough family business, generating $ 25

million in revenue last year. Because they tend to be located in poor

neighborhoods and pay donors for their blood, for-profit plasma centers

are controversial. But Stough makes no apologies.

"The plasma we collect from donors are used by pharmaceutical companies to

make life-saving drugs," Stough said. "The only way these drugs can be

made is to obtain them from donors."

Stough adds that the industry is changing, now performing rigorous testing

of donors and plasma. Some companies are opening centers in suburban

locations. And large, publicly-traded companies such as Sero-logicals Inc.

and NABI Inc. are buying up privately-held plasma centers nationwide.

Stough said he's had chances to sell, but never seriously entertained

those offers.

"I'm too slow-witted," he jokes. "I just stay in the harness and pull in

one direction."

Of course, if that were the case, Stough Enterprises wouldn't hold $ 22

million worth of real estate, most of it in Indianapolis, where Stough

opened a 40,000-square-foot retail center in 1986.

Under a dozen real estate partnerships, Stough owns property in six

states, including 80 percent of a city block near the Indiana state

capital building.

Launched in 1981 as a way to protect his centers against lease problems,

Stough's real estate entities have dabbled in commercial and residential

development. Those developments generated rental income of $ 2.5 million

last year. Stough has a five-year goal of expanding to $ 50 million in

real estate assets.

Toward that end, Stough acquired the Hanke building in 1994, saving the

historic property from demolition. His $ 5 million upgrade includes a Have

A Nice Day Cafe, and the Cell Block bar, both expected to open this

spring.

Above the bars is Stough's corporate headquarters, on the building's

9,000-square-foot second floor. Two floors above Stough are for lease.

Other real estate investments being contemplated by Stough include a $ 10

million-$ 12 million condominium project on Cayman Brac Island, a sister

island to Grand Cayman in the Caribbean.

Additional local development may also be on the horizon for Stough. He

recently bought the former Stanley Auto Parts building near Sycamore

Avenue. He's trying to lure a bar or restaurant to the building, which is

adjacent to the proposed Broadway Commons baseball site.

Q&A WITH MICHAEL STOUGH

Q: How has your management approach changed over the years?

A: I think I have a better understanding of what motivates people and what

people seek in life. I think I have more of a partnership approach to

working with people. I've come to realize that the assets of a company are

not the buildings and machinery it has. Its most important asset are the

people who work for you. In this day and time, you don't hire somebody,

you enter into a partnership with them. They agree to work with you and

they have a right to expect to participate in the fruits of the venture.

That's a lot different than what I used to think.

Q: How do you translate that into practice? Are your employees owners?

A: The way we translate it is by setting internal goals for the company

and very specifically enumerating what the benefits to them would be in

the form of bonuses if we reach those goals.

VITAL STATISTICS:

Name: Stough Enterprises Inc. Founded: 1968 Address: 1128 Main St.,

Cincinnati 45202 Telephone: 621-8728 1997 revenue: $ 27.5 million

Employees: 259 Structure: S-Corp Owners: Stough family Bankers: PNC Bank,

Star Bank Lawyer: Charles Bissinger, Vorys Sater Seymour & Pease

OFFICERS

President, CEO: Michael Stough Chief Financial Officer:. Raymond Knueven

President (SDC Design Inc.): Thomas Shumaker General Manager: Robert Rave

Regional Manager: Takiko Jones

OUTLOOK

The worldwide market for plasma-based products will grow from $ 4.6

billion in 1996 to $ 6.4 billion in 2000, according to research included

in an annual report for Clarkston, Ga.-based Serologicals Inc., a publicly

traded operator of 29 donor centers. Serologicals is the nation's

second-largest plasma company, behind Boca Raton, Fla.-based NABI Inc.

Combined, the companies posted sales of more than $ 300 million in 1996,

roughly 6.5 percent of the worldwide market. Both Serologicals and NABI

are pursuing acquisitions of donor centers nationwide. Stough Enterprises

Inc., whose seven centers posted $ 25 million in 1997 revenue, wants to

remain independent.

CHRONOLOGY

1968 * Dr. Austin Stough, a retired physician in Montgomery, Ala., starts

plasma centers in Birmingham, Ala., and Cincinnati.

1972 * Stough dies as his son, Michael, is at the University of Cincinnati

majoring in biology.

1975 * At age 25, Michael Stough leaves college to join the family

business. He's since expanded it from two to seven plasma centers.

1981 * Stough Enterprises Inc. enters the real estate development business

as a way to avoid lease hassles for its centers.

1997 * Stough gets financing to renovate the Hanke Bros. department store

building. The $ 5 million project will include Stough's 9,000-square-foot

headquarters.

|