|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

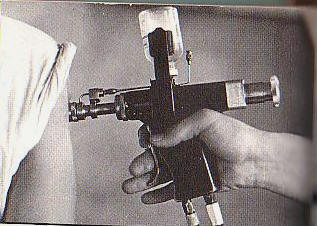

THE BLOOD BROKERS: Gilbert M. Gaul, Inquirer Staff Writer PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER; FINAL Page: A01 Last December, the Community Blood Center in Appleton, Wis., made a public appeal for blood. Residents were asked to "dig farther, wider and deeper" than ever before to keep local blood supplies at desired levels. APPLETON, Wis. - Alan Cable calls it "resource sharing."He sells blood. About 565 pints a month. To areas of the country where people are less generous about donating blood than people here in Appleton. Cable is executive director of the Community Blood Center Inc., the blood bank for this city of 58,000 people. Unlike many big-city blood banks, Appleton has no trouble meeting the needs of the four hospitals in this area to which it sells blood. The blood center hasn't had to buy blood from another center in six years. Cable said his blood center "got into resource sharing" in order to balance its inventory. Projecting the demands of the four hospitals is difficult, he has said. Sometimes those hospitals use 254 units of blood a month, and sometimes they use as many as 1,000 units, Cable said. To make certain there is always enough blood, the blood bank routinely collects more than it needs, Cable said. As that blood begins to get old, it is sold. (Blood can be stored without freezing for as long as 42 days.) Most of Appleton's blood sales are through a clearinghouse operated by the American Association of Blood Banks in Arlington, Va. Cable's center is paid $48 for each pint it sells - $10 above what it charges local hospitals. Cable said the profit helps underwrite his blood bank's operations. In 1988, Cable agreed to sell 50 pints of whole blood a week to the Central Kentucky Blood Center in Lexington. The Lexington blood bank's executive director, Walter Watts, said he bought whole blood from Appleton to extract platelets, a component that helps blood clot. The remaining red cells were then resold to the Broward Community Blood Center, near Fort Lauderdale, Fla. "To get the platelets we need, we end up having excess red cells," Watts said. "Say we need 50 (units of whole blood) a week. We'll bring in 100. "In the process, we'll move the red cells through." Lexington charged Broward $47 a pint for the red cells, Watts said. Broward, in turn, resold the blood it bought from Lexington, and thousands of other pints of red cells it purchased from other blood banks, to hospitals in New York City, Rouault said. In all, Broward bought about 15,000 pints of blood under contract in 1988, according to its president, Dr. Charles L. Rouault. Broward bought 10,000 pints more on the spot market, bringing its total purchases to 25,000 pints. Rouault is one of only two doctors licensed to sell blood in New York City, records show. He has connections to hospitals there, he said, from his days as a medical resident and knows most of the blood-bank directors. Reports filed in 1988 with the New York State Department of Health show that at least four hospitals purchased blood from Rouault: Mount Sinai Medical Center, Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, New York University Hospital and Lenox Hill Hospital. On average, Broward paid $42 a unit for the 25,000 units it bought from Lexington and the other blood centers; after markups, Broward sold that blood for $63 a unit, earning a profit of $525,000, Rouault said. Rouault says he is not making excess profits. "If we were profiteering, we would charge $72, not $63." PHOTO (1), 1. Dr. Charles L. Rouault's center sells blood to New York City hospitals. (The Philadelphia Inquirer / LARRY C. PRICE) Blood sustains life itself, transporting vital oxygen and nutrients to body tissues and removing carbon dioxide and other wastes. It also helps fight infections and generates clotting proteins that prevent undue blood loss from cuts. Roughly 7 percent of the average American man's body weight is made up of blood - about 10 to 12 pints. The average American woman has about nine pints. Each year, more than 4 million Americans receive transfusions, using about 13.5 million units of blood. The number of units transfused varies from as little as one pint to dozens of pints for such procedures as liver transplants. Blood can be stored without freezing for up to 42 days. Here are some terms used in the blood industry: UNIT. A measurement of blood; for example, a unit of red cells or a unit of plasma. The volume in a unit varies, depending on the blood component. WHOLE BLOOD. Consists primarily of red blood cells, plasma and platelets. A unit of whole blood is equal to 500 milliliters, or about a pint. RED CELLS. Transport oxygen through the body and are used to fight anemia. A unit of red cells is equal to about 250 milliliters, or about half a pint. PLASMA. The solution in which red cells are suspended. Transports nutrients and bolsters the immune system. The source of a number of important proteins that promote clotting and fight infections. A unit of frozen plasma is equal to about 240 milliliters, or nearly half a pint. PLATELETS. Cause blood to clot, are prescribed for

patients whose own cells have been destroyed during therapy

for leukemia and other forms of cancer. Platelets may be

recovered from whole blood or drawn separately from donors

in a process called hemapheresis. A unit of platelets is

equal to about 50 milliliters.

"We've never had it quite this tough," Alan W. Cable, executive

director of the nonprofit blood bank, told the local newspaper. The citizens did dig deep; last year, 15,000 pints of blood were

donated by Appleton residents to help save the lives of their

friends and neighbors.

What they didn't know, though - don't know to this day - was that

the same month the blood bank was appealing for blood, it sold 650

pints - half its monthly blood collection - at a profit to other

blood banks around the country. Or that last year the blood center in Appleton contracted to sell

200 pints a month to a blood bank 528 miles away in Lexington, Ky.

Or that Lexington sold half the blood it bought from Appleton to

yet a third blood bank near Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Which in turn sold

thousands of pints it bought from Lexington and other blood banks to

four hospitals in New York City. What began as a generous "gift of life" from people in Appleton

to their neighbors ended up as part of a chain of blood brokered to

hospitals in Manhattan, where patients were charged $120 a pint.

Along that 2,777-mile route, human blood became just another

commodity. The buying and selling of blood has become big business in

America - a multibillion-dollar industry that is largely unregulated

by the government.

Each year, unknown to the people who give the blood, blood banks buy

and sell more than a million pints from one another, shifting blood

all over the country and generating an estimated $50 million in

revenues. It is not uncommon for some blood banks to broker between 20

percent and 40 percent of what they collect. In Appleton, nearly

half the blood collected from donors in the last two years was sold

outside the area. In Waterloo, Iowa, the American Red Cross sold six

of every 10 pints collected last year to other blood banks. They do it, blood bank officials say, to share a limited

resource. Although they have a monopoly, blood banks in dozens of

cities - Philadelphia among them - are unable to collect as much

blood as they need. To cover their shortfalls, they buy blood from

centers, such as Appleton, that collect more than they need. Nobody disputes the value of sharing blood. But in the last 15

years, this trading in blood has become a huge, virtually

unregulated market - with no ceiling on prices, with nonprofit blood

banks vying with one another for control of the blood supply, with

decisions often driven by profits and corporate politics, not

medical concerns. In this marketplace, blood, a vital resource, gets less

government protection than grapes or poultry or pretzels. Dog

kennels in Pennsylvania are inspected more frequently than blood

banks.

And donors are rarely told what happens to their blood.

"People are being fooled," said Dr. Aaron Kellner, recently

retired president of the New York Blood Center, which buys 300,000

pints of blood a year. "Nobody is telling them that their blood is

going to us. They would be furious if they knew about it."

"I didn't give blood so someone else can make money from my blood. I

gave it to be used at the least expense by anyone who would need

it," Lynne Nelson, 24, of Appleton, said when told by a

reporter recently that some blood collected there is sold elsewhere.

It is not just a question of candor. As more and more blood is

traded around the country - changing hands two, three or four times

- it becomes much more difficult to keep track of which blood came

from where, or from whom. As the collection and distribution

network becomes more complex, chances of errors multiply. In fact,

errors at blood banks have increased dramatically in the last two

years as overworked technicians struggle to keep up with more and

more tests for detecting viruses in the blood, including those for

hepatitis and AIDS. The potential for fatal mistakes is "a ticking time bomb," said

Frank E. Young, commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration.

Most blood sales take place through clearinghouses operated by

the American Red Cross and other nonprofit blood-collecting groups.

But there is also a spot market - not unlike the one for oil - where

hundreds, possibly thousands, of sales occur each year. "It functions rather like the NASDAQ," a national system for

trading over-the-counter stocks, said Dr. Charles L. Rouault,

president of the Broward Community Blood Center near Fort

Lauderdale. "You pick up the phone and call somebody you know." No one - not the federal government, not the blood banks

themselves - knows for sure how much blood is bought and sold on the

open market. There are no requirements that sales be reported; no

government agency keeps track. All of which should be of grave concern to Americans, for the

very safety of the nation's blood supply is at stake. A FLAWED SYSTEM A yearlong examination of the American blood system by The

Inquirer has uncovered major flaws in the way blood is collected,

distributed and regulated. Among the findings: * The federal government has failed to adequately police the

blood business, in essence allowing the industry to regulate itself.

* With no one overseeing prices, blood banks are free to charge

hospitals whatever the market will bear. Hospitals add their own

markups, often unrelated to their actual costs. And blood centers

facing shortages are left to scramble to find blood. * Prices vary widely from region to region, and sometimes within

a region. Patients are charged by hospitals up to $300 a unit for

blood that was given free by donors. * Nonprofit blood banks compete directly with commercial

companies in some lucrative areas of the blood business. Their

commercial competitors say the blood banks enjoy an unfair business

advantage because they are exempt from paying taxes.

* At least 40,000 people a year contract hepatitis through blood

transfusions. Yet until the AIDS epidemic, doctors routinely ordered

transfusions for patients undergoing surgery, often unnecessarily

exposing them to risks of blood-borne infections. * Blood collectors say they have done everything possible to

ensure the safety of the blood supply.

Yet confidential documents show the industry ignored or delayed

using readily available tests and procedures to make blood and

transfusions safer. * At a time when AIDS was showing up in the blood supply in the

early 1980s, the FDA reduced its inspections of blood-collecting

facilities from once a year to once every two years. * Thousands of pints of suspect blood and other blood components

have been released by blood banks and commercial plasma centers as a

result of testing errors, computer problems and other mistakes. This haphazard system exists because the United States has failed

to develop a comprehensive blood program that ensures adequate, safe

supplies to all regions of the country at fair prices. The United States is one of only a handful of Western nations

that leave the collection and distribution of blood scattered among

a patchwork of private and quasi-public groups. "What we have is not so much a system as a non-system," said

Norman R. Kear, administrator of the Red Cross' blood center in Los

Angeles. "Blood-collecting groups like the Red Cross cooperate when

it is in their interest to cooperate, and when it's not in their

interest, they fail to cooperate." Unless they stopped making what a rival blood bank said were disparaging and defamatory statements to doctors, hospital officials and patients, "our client has instructed us to consider a civil lawsuit against you for substantial damages," a letter said. It was written by a lawyer representing the Broward Community Blood Center in Lauderhill, Fla., near Fort Lauderdale. But Dr. Charles L. Rouault, the blood bank's president, freely acknowledges he was the force behind it. A blood war is going on in South Florida. "Dr. Tomasulo and I have been at war for years," Rouault said. "We have been competing in virtually every way one could compete in the blood-banking industry: supply, price, quality of service, range of services. There's not much more." It is a battle that in the last decade has spilled over to the board rooms and surgical suites of some of Florida's most prestigious hospitals, has divided school officials and companies and has left many of those involved angry and confused. South Florida is one of only a handful of major metropolitan areas in the nation where blood banks compete. Economists and other observers say competition would be good for blood banks, leading to lower prices. But what is happening here could cause second thoughts. Some blood bank administrators say they are appalled by the rivalry in South Florida. "It's turned into a gasoline price war," said Norman Selby, who formerly ran the New York Blood Center. The competition between Rouault and Tomasulo has caused hard feelings and forced people who deal with the blood banks to take sides. "It's a mess," Rouault said. "The blood business down here . . . is the heart of darkness." Each blames the other for allowing the situation to get out of hand and wanting to put his rival out of business. Tomasulo said Rouault had a "clear intention to increase market share" at his expense and had raided some of his blood bank's traditional donor groups. Rouault countered that the Red Cross' South Florida Blood Services raided Broward's groups first, and complained that Red Cross has a "monopolistic mind-set. They want to operate a cartel." The two presidents locked horns again this year when Tomasulo requested permission from the Broward County school board to collect blood in high schools there. Rouault protested, arguing that he had spent years building up a successful program in the schools. An arbitrator, Circuit Judge John A. Miller, scolded both in a February report that supported most of Rouault's contentions. "There has been a long history of negotiations . . . to establish some kind of joint venture, but success has been thwarted by each wishing to control the other. . . . It's territorial rights." Therein lies the real story of this blood feud. What is ultimately at stake is control of a product worth millions of dollars. "Leaving Broward and probably Palm Beach (Counties) would have a grave negative impact on our bottom line," a confidential Red Cross analysis prepared this summer said. In 1988, South Florida Blood Services in Miami collected approximately 105,000 pints and had revenues of more than $10 million. A salary figure for Tomasulo was not available. However, a 1987 tax return filed by the Red Cross shows Tomasulo was paid $166,775 in salary and benefits. Broward collected about 60,000 pints of blood in 1988 and had revenues of more than $5 million. Rouault was paid about $125,000 and had the use of a car provided by the blood bank. Rouault contends that the Red Cross in Miami has invaded Broward and Palm Beach Counties because it can't collect enough blood in its home turf of Dade County to meet the needs of the 61 hospitals it serves. In 1988, it had to buy about 40,000 pints of blood, at a cost of $1.5 million, from other centers, according to Red Cross documents and interviews. "If I couldn't collect enough blood . . . I would be embarrassed," Rouault said. "We have a healthy, financially viable operation here and I don't think Peter likes to be reminded of that fact." Tomasulo said his blood center has "made great strides toward becoming (self-) sufficient" in the last decade. "Miami is like a number of other urban areas. There are many challenges to collecting blood." Until July 1986, South Florida Blood Services was a private, nonprofit blood bank with no affiliations. But that month, Tomasulo and his board of directors agreed to merge with the Red Cross. The decision was prompted by many factors, including the competition with Broward, Tomasulo said. As part of the merger, the Red Cross agreed to supply Tomasulo with blood to make up his deficits. Tomasulo, in turn, agreed to not buy blood from non-Red Cross blood banks, including Rouault's. Following the merger, South Florida Blood Services cut its price to compete with Broward, improved its collections in Dade County and expanded its efforts to collect and sell blood in counties to the north - including Broward and Palm Beach Counties. "Why they would want to sell blood here when they can't even meet their own needs in Dade is beyond me," said John H. Flynn, president of the Palm Beach Blood Bank in West Palm Beach. Flynn has formed an alliance with Rouault to fight Tomasulo. For Rouault, the South Florida Blood Services and Red Cross merger was a nightmare come true. "We can compete successfully with Peter Tomasulo, but we can't compete against all of Red Cross," he said. In 1986, Rouault began selling blood to hospitals in New York City and northern New Jersey to help finance his battle. Last year he brokered about 25,000 pints of blood, worth nearly $1.5 million. Tomasulo and Red Cross management at national headquarters in Washington were not happy when they found out what Rouault was doing. Rouault said they "tried to pressure some of the hospitals into not buying the blood." Tomasulo denied that charge but acknowledged calling at least one blood-bank director at a New York hospital. "We would like it (the New York sales) stopped because it provides them a tremendous economic advantage," he said. More recently, a Red Cross official complained to the Internal Revenue Service that the Broward blood bank had refused to show him its tax return as required by law. (Even though they pay no taxes, nonprofit blood banks file statements of their income and expenses with the IRS.) "We drove up there and asked to see it (the tax return) and their administrator told us it wasn't there," said Michael G. Hunter, financial administrator for the Miami Red Cross. "It's a natural course of doing business to want to know how your competition is doing. That's what I was doing. I wanted to know what is their financial position, to make comparisons." Responded Jeffrey McNally, administrator of the Broward Community Blood Center: "We'd be happy to turn over our financial information if they would turn over theirs." CAPTION: PHOTO (2), 1. The Broward center's Rouault

accuses the Red Cross of having a "monopolistic mind-set."

(The Philadelphia Inquirer / LARRY C. PRICE), PHOTO (5), 1. Tyson Thompson, 17, gives blood at Broward Community Blood Center, near Fort Lauderdale. (The Philadelphia Inquirer / LARRY C. PRICE), 2. Technician Claudene Talbott catalogues units of whole blood at the Broward blood center. (The Philadelphia Inquirer / LARRY C. PRICE), 3. Barbara Phillips enters a bloodmobile in Appleton, Wis.; 15,000 pints of blood were given there in 1988. (Special to The Inquirer / ALLEN FREDRICKSON), 4. At the Red Cross center at 23d and Chestnut Streets, an employee prepares freshly collected blood for processing. (The Philadelphia Inquirer / SHARON J. WOHLMUTH), 5. Medical technician Judy Goodermote monitors the plasma machine as Bob Barlament donates blood in Appleton. (Appleton Post-Crescent), MAP (1), 1. Who buys and sells blood: The top five blood centers (SOURCE: Interviews with blood bank officials; The Philadelphia Inquirer / KIRK MONTGOMERY), CHART (3), 1. From donor to patient: How blood is collected and priced (SOURCE: Crozier Chester Medical Center, American Red Cross; The Philadelphia Inquirer), 2. What one hospital charges for blood (SOURCE: Crozier Chester Medical Center, American Red Cross; The Philadelphia Inquirer), 3. Prices charged by blood banks for a pint of red blood cells, 1988 (SOURCE: Interviews with blood bank officials, American Red Cross; The Philadelphia Inquirer / KIRK MONTGOMERY) Not for commercial use. Solely to be used for the educational purposes of research and open discussion. |

|

Site Map

For problems or questions regarding

this Web site contact

|

|

|