Problems Persist With Red Cross Blood Services

Jessica Kourkounis for The New York Times

In 2004, auditors found that the Red Cross’s operation in Philadelphia failed to recall some 600 units of blood collected using improper methods. In 2004, auditors found that the Red Cross’s operation in Philadelphia failed to recall some 600 units of blood collected using improper methods.

By

STEPHANIE STROMPublished: July 17,

2008

For 15 years, the

American Red Cross has been under a

federal court order to improve the way it

collects and processes blood. Yet, despite

$21 million in fines since 2003 and repeated

promises to follow procedures intended to

ensure the safety of the nation’s blood

supply, it continues to fall short.

Quality

control has been a problem at

the Red Cross.

The situation has proved so frustrating

that in January the commissioner of food and

drugs attended a Red Cross board meeting — a

first for a commissioner — and warned

members that they could face criminal

charges for their continued failure to bring

about compliance, according to three Red

Cross officials who attended the meeting and

requested anonymity because Red Cross policy

prohibits public discussion of its meetings

with regulators.

“If fear is a motivator, we’re happy to

help out in that way,” said Eric M.

Blumberg, deputy general counsel at the

Food and Drug Administration, though he

declined to confirm what the commissioner,

Andrew C. von Eschenbach, said at the

meeting.

Some critics, including former Red Cross

executives, have even suggested breaking off

the blood services operations from the rest

of the organization, as the Canadian Red

Cross did a decade ago.

The problems, described in more than a

dozen publicly available F.D.A. reports —

some of which cite hundreds of lapses —

include shortcomings in screening donors for

possible exposure to diseases; failures to

spend enough time swabbing arms before

inserting needles; failures to test for

syphilis; and failures to discard

deficient blood.

In some cases, the lapses have put the

recipients of blood at risk for diseases

like

hepatitis,

malaria and syphilis. But according to

the food and drug agency, the Red Cross has

repeatedly failed to investigate the results

of its mistakes, meaning there is no

reliable record of whether recipients were

harmed by the blood it collected.

The Red Cross, which controls 43 percent

of the nation’s blood supply, agrees that it

has had quality-control problems and is

working to fix them. Both its officials and

the drug agency point out that none of the

identified problems involve the most serious

category of infractions. For instance, the

Red Cross does a good job of testing for

H.I.V. and

hepatitis B, officials on all sides

agree. And in general, Red Cross blood is

regarded as some of the safest in the world.

Still, the drug agency says, the problems

that remain in screening donors and

following protocols for collection add

unnecessary risk to blood transfusions,

almost five million of which were done in

2007, according to the National Heart, Lung

and Blood Institute.

“This is a critical piece of the public

health infrastructure,” Mary A. Malarkey,

director of the Office of Compliance and

Biologics Quality at the drug agency, said

in an interview. “I know it’s difficult to

get so many people trained and properly

supervised, but it has to be done.”

This week, the agency sent the Red Cross

the results of yet another recent

investigation that makes Ms. Malarkey’s

point: From December 2006 to April 2008, the

Red Cross distributed more than 200 blood

products that it had already identified as

problematic, according to the investigation

report.

A Troubled History

While many Americans see the Red Cross as

the ubiquitous organization that responds to

disasters big and small, its disaster-relief

operation, which spends $400 million to $500

million annually, is small compared with its

blood business, which generated $2.1 billion

in revenue in the fiscal year that ended in

June 2007.

In fact, the Red Cross is the world’s

largest single steward of blood, more than

twice the size of the second-largest known

blood collection operation. The rest of the

world’s blood supply is controlled by dozens

of smaller organizations, only three of

which have ever been under F.D.A.-requested

consent decree.

After years of quiet complaints about the

Red Cross’s blood business, the F.D.A.

reluctantly decided to go public with its

concerns in 1993, obtaining a consent decree

that required the Red Cross to strengthen

quality control and training and improve its

ability to identify, investigate and record

problems.

“It was one of the hardest things I did

as commissioner,” said Dr.

David A. Kessler, the F.D.A.

commissioner from 1990 to 1997. Dr. Kessler

said he had agonized that the move would

cause undue alarm.

The news media, however, barely made note

of it.

Fifteen years later, that consent decree,

toughened in 2003 to allow the F.D.A. to

impose fines for failing to properly

identify, handle and report quality control

problems, has produced only modest

improvements, food and drug officials said.

“Leaving aside who’s at fault here, it’s

not working,” said Dr. Kessler, now a

professor of pediatric medicine at the

University of California, San Francisco.

“Whether it’s that the American Red Cross

just doesn’t get it, whether it’s that the

relationship between the regulator and

regulated is beyond the point of repair is

immaterial. It’s just not working.”

Dr. Kessler said Congress should

intervene at this point. (Page 2 of 3)

Dr.

Bernadine Healy, the former chief

executive of the Red Cross who made

repairing the organization’s blood

operations a paramount goal, said the best

solution might be to spin off the Red

Cross’s blood services.

Jessica Kourkounis for The

New York Times

Despite a

federal court order to improve,

the Red Cross has had problems

for years ensuring the safety of

the blood it collects and

processes.

Jessica Kourkounis for The

New York Times

“Two-thirds of the revenue base of the

Red Cross is blood, yet the Red Cross is run

by people who think of it as primarily a

disaster-relief organization, relegating

blood to stepchild status,” Dr. Healy said.

“When is the last time you saw a Red Cross

fund-raising appeal for money to make the

blood supply safer or support its blood

research?”

Dr. Healy said she tried to start such a

fund-raising program when she ran the Red

Cross, but met internal resistance to it.

The Red Cross has toyed with selling off

its blood operations, or otherwise

decoupling them from its disaster work, but

has never done so, in part because of a

belief that the billions in revenue from

blood has subsidized its disaster

operations. But its financial systems are so

antiquated that no one really knows.

“I can’t tell you that for sure because I

can’t find it out,” said Kevin M. Brown, the

Red Cross’s chief operating officer. “I wish

I could.”

Mr. Brown noted, however, that the blood

business was an integral part of the Red

Cross. “It is consistent with our overall

mission, which is saving lives,” he said.

“Having an ample and safe blood supply is

critical to that mission.”

Failing to Act

The frustrations of dealing with the Red

Cross are illustrated by the story of

Michelle Hoyte, a whistle-blower who was

first ignored, then dismissed.

Ms. Hoyte led a team of auditors who

conducted a routine visit to the Red Cross

blood services operation in Philadelphia in

2004. The team discovered that the facility,

with the approval of a senior executive at

the national headquarters in Washington, had

decided not to recall some 600 units of

blood collected using improper methods.

Such mistakes must be reported in writing

to the F.D.A. within 15 days of detection,

and the blood must be recalled. But Ms.

Hoyte spent six months pleading with various

supervisors to report the problem, first

identified on Dec 18, 2003. Then she was

fired.

“It wasn’t just that I thought it was the

right thing for them to do; they are

required to tell the F.D.A. under the terms

of the consent decree,” Ms. Hoyte, who

worked for the F.D.A. before joining the Red

Cross, said in an interview. “They didn’t

want to hear it.”

Ms. Hoyte, who unsuccessfully sued the

Red Cross for wrongful termination, had

received “excellent performance appraisals,”

according to the lawsuit, and received a

bonus and merit raise in the two years

before her firing.

The Red Cross contends that her dismissal

had nothing to do with her insistence on

abiding by the court order. It said in court

papers that she had been warned of

shortcomings in her performance.

The Red Cross also defended its handling

of the episode. “They followed the process

and did what they should have done,” said

Eva Quinley, the senior vice president for

quality and regulatory affairs at the Red

Cross.

But the Red Cross did not recall the

components produced from that blood until

Feb. 23, 2005, 14 months after the problem

was discovered, according to an F.D.A.

report. By then, those components would have

been used or discarded, and whether they

caused any problems for patients is unknown.

Determining how often, if ever, blood

supplied by the Red Cross has been

responsible for serious health problems is

difficult. F.D.A. documents rarely spell out

the consequences of the failures they

catalogue, a reflection, to some degree, of

the agency’s concern about alarming the

public. But often they simply do not know.

“Patients who get blood transfusions tend to

be pretty sick,” Dr. Healy said. “If they

spike a

fever post-transfusion, no one is likely

to suspect that the blood caused it.”

Various records of F.D.A. inspections and

correspondence with the Red Cross highlight

poor follow-up, including falsified records.

On Nov. 19, 2001, for example, a patient

receiving blood bought from the Red Cross’s

greater Chesapeake and Potomac region, which

serves the Washington area, died of

hepatitis, according to an F.D.A. report.

The agency concluded that the Red Cross had

failed to perform a thorough investigation.

Furthermore, the drug agency found that

the Red Cross had failed to investigate 134

cases of suspected post-transfusion

hepatitis that occurred across all its

regions from January 2000 to June 2002.

Ms. Quinley said procedures had been

changed since then in an effort to ensure

that such cases would be investigated.

A Fractured System

(Page 3 of 3)

Until 1991, Red

Cross blood

operations were

largely controlled

by its regional

chapters, which

operated 53 blood

centers in vastly

different and often

idiosyncratic ways.

That year,

Elizabeth Dole,

then chief executive

of the Red Cross,

announced a sweeping

overhaul that

wrested control of

the blood operations

from the chapters

and reorganized them

into 10 regions,

which were expected

to adhere to a

uniform set of

standards and

procedures.

That event is

still referred to

among many at the

Red Cross as “the

Divorce,” a measure

of the

organization’s

entrenched culture.

While Mrs. Dole

won praise for

taking a bold step

to address a long

history of sloppy

testing and record

keeping that raised

concerns among

regulators and the

public about blood

being potentially

contaminated with

H.I.V., chapters and

their staff and

volunteers saw it as

an effort by the

national

headquarters to

control the vast

amount of money the

blood services

generate.

That legacy

persists.

“We have never

truly moved away

from independence to

national, central

standards,” said J.

Chris Hrouda,

executive vice

president and a

20-year veteran of

the Red Cross’s

biomedical services,

as the blood

operations are

known.

Nor did anyone

anticipate the cost

and difficulty of

the reorganization,

current and former

executives said. At

first the project

was budgeted at $120

million, but the

cost of developing a

centralized database

has run to at least

$1 billion so far,

according to

estimates by former

executives. The

database would make

it easier to track

down flawed blood

components and to

flag donors who have

been previously

screened out because

of diseases or

travel to places

where malaria is

common.

“There is no

system to meet our

needs,” Mr. Hrouda

said. “We are six

times the size of

the next-largest

blood operations,

and clearly that’s a

hindrance.”

A small company

in Paris, Mak-System

International Group,

is working to create

such a system, but

Mr. Hrouda had no

estimate of when it

would be up and

running.

Thus, the Red

Cross’s current

blood operations, 36

regions grouped into

seven divisions

served by five

testing

laboratories, are

still controlled by

different systems

that cannot easily

“talk” to one

another.

In the meantime,

the Red Cross has

incorporated

technology intended

to help it prevent

mistakes when blood

is collected.

The most frequent

errors cited by

F.D.A. investigators

involve failing to

ask donors questions

that would reveal

their ineligibility

to give blood. For

instance, an

interviewer forgets

to ask a donor

whether he has

traveled in an area

where malaria is a

problem. So

increasingly, donors

fill out online

questionnaires,

which helps ensure

that all required

questions are

answered.

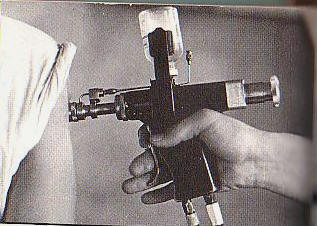

Blood collection

is also error prone,

governed as it is by

strictly prescribed

procedures. After

phlebotomists locate

a vein, they must

scrub a

3-inch-by-3-inch

area with antiseptic

soap for 30 seconds,

then use an

antiseptic swab and,

starting at the

point where they

will insert the

needle, work

outwards in

concentric circles.

They must then allow

the area to dry for

precisely 30 seconds

before inserting the

needle.

To improve that

process, Red Cross

phlebotomists

recently began

wearing electronic

devices that time

each of those steps.

The organization

is also improving

oversight on the

mobile units used to

collect roughly 80

percent of the blood

it processes by

assigning full-time

supervisors.

Such measures,

however, are

undercut by high

turnover among

employees, who are

paid little better

than minimum wage,

former executives

say.

Mr. Hrouda said

there was no plan to

address high

turnover. “We think

we’re able to

recruit people at

the wages we pay and

are good at training

them,” he said.

The F.D.A.,

however, sees the

main problem

differently. “Size

is no longer an

excuse,” said Mr.

Blumberg, the

agency’s deputy

general counsel.

Ms. Malarkey, of

the F.D.A.’s Office

of Compliance and

Biologics Quality,

said: “Right now,

the biggest issue

confronting the Red

Cross is what we

refer to as their

problem management.

They have standard

operating procedures

by which they should

be able to

investigate,

evaluate, correct

and control to

prevent recurrence

of the issues we

have identified

again and again, but

they have a lot of

difficulty

implementing those

procedures and,

frankly, in having

people follow them.”

Ms. Malarkey said

a recent “adverse

determination

letter,” the process

through which the

F.D.A. informs the

Red Cross of

violations it has

identified and

demands payment of

fines, illustrated

her point.

In that letter,

dated Feb. 8, the

drug agency listed

113 “events”

involving 4,094

flawed blood

components that were

recalled by 15 of

the Red Cross’s 36

regions. The recalls

occurred largely

from April 15, 2003,

to April 15, 2006.

(It is not uncommon

for letters to list

hundreds of

infractions — one

2005 letter

identified more than

22,000 flawed blood

components that were

recalled — and

recalls do not mean

every blood product

is returned.)

“We are not

seeing what we were

seeing in the late

1980s and early

1990s, where

unsuitable blood was

routinely being

released,” Ms.

Malarkey said, “but

they still need to

make more progress,

and we would like to

see that progress

made quickly.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/17/us/17cross.html?pagewanted=3&_r=2&hp&adxnnlx=1216289519-PakcZC8LgRzjzM9JHjlj9g

Related:

Times Topics: American Red Cross

Enlarge This Image

Jessica Kourkounis for The

New York Times

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/organizations/a/american_red_cross/index.html

|