![]()

Why Are Prescription Drugs So

Expensive? Big Pharma Points To The Cost

Of Research And...

Harry Hooks served in the Vietnam War for one year and is long retired from the military, but he is still paying a high price for his service. The 66-year-old, who lives in Pennsville, New Jersey, was diagnosed with hepatitis C in 2004 and has struggled with painful symptoms ever since.

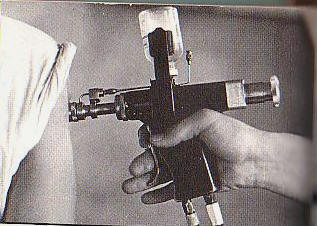

During the war, veterans may have been infected with hepatitis C while receiving vaccinations with rapid-fire tools known as jet injectors. If Hooks didn’t get the virus from those vaccinations, he says it was likely from the 40 units of blood he received in a transfusion after he was “blown up” on duty in Vietnam in 1969.

Decades later, the virus causes his hands and feet to throb in pain or go numb, a condition known as peripheral neuropathy. He often feels fatigued. When he heard about new hepatitis C drugs that were coming on to the market last year and promised a remarkable cure rate, he was eager for himself and fellow vets he had met through a support website called hcvets.com to receive treatment.

But he was also wary. Hooks started warning other vets not to get their hopes up about receiving the drugs anytime soon -- it only took one look at the list price of these expensive new medicines for Hooks to suspect that the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs would struggle to pay for them.

Today, Hooks has not yet received any of the new medications, but the Department of Veterans Affairs has stopped enrolling new hepatitis C patients for the drugs due to budget constraints. The VA initially reallocated $700 million to cover the costs for 20,000 veterans but asked Congress for another $400 million in a letter sent last week.

“They ran out of money,” Hooks says. “Anybody that was in line to get access will have to wait.”

Hooks is one of 3.2 million Americans who have hepatitis C, a viral infection that causes the liver to become inflamed. It is spread through contact with the blood of another infected person and over a lifetime, it can cause scarring of the liver known as cirrhosis or liver cancer.

A drug named Sovaldi cures more than 90 percent of patients with hepatitis C who take a daily pill for just 12 weeks with minor side effects. Those results made it the obvious choice for patients such as Hooks, who had already tried multiple drugs, including ribavirin and interferon, which only promise a 50 percent cure rate.

The Food and Drug Administration approved Sovaldi in December 2013, but when Gilead Sciences announced the price -- $84,000 for 12 weeks of treatment, or $1,000 per 400 mg pill – patients and their insurance companies balked. Ribavirin had cost just $1,700 for a 48-week treatment.

Over the last few years, this scenario has played out again and again: A company receives FDA approval for a new drug, but when the company reveals the list price, patients who were hoping for a better life suffer from sticker shock.

“What you have now is an onslaught of highly effective but very, very expensive drugs and vaccines,” Soeren Mattke, a public health policy expert at the nonprofit RAND Corporation, says.

The high cost of new drugs including Sovaldi has prompted patients, senators, insurers and physicians to question the pricing tactics of drug companies.

Gilead has received particularly heavy scrutiny over Sovaldi, because unlike specialty medicines for rare conditions, Sovaldi could be prescribed to millions of patients. The magnitude of the drug’s total cost could overwhelm an insurer or an entire healthcare system.

Last year, U.S. senators demanded Gilead hand over all internal documents related to the price of Sovaldi for a federal investigation. The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority has also filed a class action lawsuit against the company, claiming unjust enrichment and violations of the Affordable Care Act.

Still, the mechanisms that drug companies use to set prices remain a closely held trade secret. And despite the pushback, Gilead debuted another treatment for hepatitis C in 2014 named Harvoni which costs even more -- $94,500.

As the industry repeatedly demands extraordinary prices from patients and taxpayers, it prompts the question -- how, exactly, does a pharmaceutical company determine the price of a new medicine?

Pharmaceutical companies operate largely outside of traditional market forces, and experts suggest that one variable has an outsized influence in setting the price for most medicines in the U.S. – how much patients and their insurers are willing to pay.

These rules don’t apply

The story of how drugs came to carry the eye-popping price tags of today dates back at least 30 years. Glaxo Holdings Inc., now part of GlaxoSmithKline, introduced Zantac to treat ulcers as a competitor to SmithKline’s Tagamet in 1983. Despite the fact that the medications were nearly identical, Glaxo priced Zantac 56 percent above Tagamet. The company’s former chairman, Sir Paul Girolami, believed that a high price could persuade consumers to pay for the marginal value of the medicine over Tagamet. And it worked -- Zantac soon overtook Tagamet to become the world’s best-selling medicine. By 1989, Zantac had captured 53 percent of the American market as compared to Tagamet’s 28 percent.

Drug executives often say prices reflect the fact that companies lay out an average of $2.6 billion and spend 10 to 15 years to bring a single drug to market. The industry’s trade group, Pharmaceutical Researchers and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), points out that only 20 percent of drugs earn back research and development costs and a recent MIT study showed that companies lost about $26 million on each new drug they developed from 2005 to 2009.

But Andrew Witty, the CEO of GlaxoSmithKline has called these billion-dollar R&D figures “one of the great myths of the industry" because they include the cost of failed experiments as well as successes. And the analysts at the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development who reported the $2.6 billion figure last fall were criticized for failing to disclose their methods.

There’s no doubt that pharmaceutical companies spend vast amounts of money to develop new drugs but to Rena Conti, a health economist at the University of Chicago, the argument that a drug’s price is based primarily on these costs doesn’t ring true -- particularly in the case of Sovaldi.

Gilead acquired the rights to Sovaldi when it purchased a company called Pharmasset, just a year before the medicine received FDA approval. By that time, Pharmasset had already completed much of the research and showed that it could sell the drug at a profit for $36,000 per treatment cycle, according to documents filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Gilead purchased Pharmasset for $11 billion in 2011. In 2014, Sovaldi’s first year on the market, the drug generated $10.3 billion in sales.

Conti says even if drug prices did reflect costs, that price should be close to the variable cost of production, or the cost that goes into making the next bottle of pills, rather than a company’s entire research budget. Production costs are certainly not zero, but on average, generic drugs – which offer the best approximation of variable costs -- are priced at 80 to 85 percent below brand name medicines.

For example, the price of Lipitor to treat high cholesterol dropped from more than $5 per pill to 31 cents– a 95 percent reduction -- once the drug faced with generic competition beginning in 2011. In the case of Sovaldi, an analysis led by the University of Liverpool in the U.K. showed that a 12-week course of the drug could be manufactured for just $68 to $136.

Uwe Reinhardt, a health economist at Princeton University, points out that price only reflects costs when competition between companies brings a price within close range of the costs it took to produce a good. The FDA protects pharmaceutical companies from competition by prohibiting rival products from coming onto the market for five to seven years after a drug is approved.

“In drug companies, you do not have perfect competition -- you have artificial monopolies,” he says.

In another twist, the cost of a drug is largely divorced from a patient’s pocketbook. Therefore, drug companies worry less about whether a single person can afford the product than whether a major insurance company or healthcare system will pay for it.

Taken together, these exceptions mean the price of medicine is not limited by two of the primary forces that keep the costs of most U.S. consumer goods in check -- competition and affordability.

“I believe in economics as a way of explaining why things happen but nearly every assumption that is based on a normal economic market is not present in this market,” Stephen Schondelmeyer, an expert in pharmaceutical pricing at the University of Minnesota, says.

That leaves one remaining force that Reinhardt says is largely responsible for shaping drug prices – willingness to pay. To set a price for a new drug, pharmaceutical companies work backward from the highest possible amount that consumers, insurers or healthcare systems will pay in order to have it.

"The drug company is saying -- ‘We invented something that saves lives. What is it worth to you?’” Reinhardt says.

To his point, a recent analysis by the National Institutes of Health published in JAMA Oncology found no connection between the effectiveness and price of 51 cancer drugs, and concluded that drug prices “simply reflect what the market will bear.” Physicians at the Mayo Clinic reinforced that point in a recent paper in Mayo Clinic Proceedings that also refuted four of the pharmaceutical industry’s main arguments for why drug prices are so high.