|

Hepatitis C

Virus Transmission at an

Outpatient Hemodialysis Unit

--- New York, 2001--2008

In July

2008, the New York State

Department of Health (NYSDOH)

received reports of three

hemodialysis patients

seroconverting from

anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV)

negative to anti-HCV

positive in a New York City

hemodialysis unit during the

preceding 6 months. NYSDOH

conducted patient interviews

and made multiple visits to

the hemodialysis unit to

observe hemodialysis

treatments, assess infection

control practices, evaluate

HCV surveillance activities,

review medical records, and

conduct interviews with

staff members. This report

summarizes the results of

that investigation, which

found that six additional

patients had HCV

seroconversion during

2001--2008 and that the

hemodialysis unit had

numerous deficiencies in

infection control policies,

procedures, and training. Of

the total of nine

seroconversions, the sources

for four HCV infections were

identified phylogenetically

and epidemiologically as

four other patients in the

unit. The unit's policy for

routine patient testing for

HCV infection was not in

accordance with CDC

recommendations, and the few

recommendations followed

were not implemented

consistently. Hemodialysis

units should routinely

assess compliance to ensure

complete and timely

adherence with CDC

recommendations to reduce

the risk for HCV

transmission in this

setting.

The

hemodialysis unit was a

large, for-profit,

outpatient facility treating

70--100 patients daily at 30

dialysis stations. On May

24, 2008, the New York City

Department of Health and

Mental Hygiene informed

NYSDOH of a confirmed HCV

seroconversion in one

patient receiving chronic

hemodialysis treatment at

the unit. On July 1, the

unit reported two additional

HCV seroconversions directly

to NYSDOH. Interviews

conducted by NYSDOH with the

three patients who

seroconverted revealed no

other common health-care

exposures or behavioral risk

factors. In addition, none

of the three had been

informed by the hemodialysis

unit of their HCV

infections. Initial site

visit findings by NYSDOH

documented poor infection

control practices and

oversight. Specific

recommendations addressing

deficiencies were provided

to the unit's administrative

staff members at the initial

site visit and throughout

the investigation. An

epidemiologic investigation

subsequently was undertaken

to identify additional

patients with HCV infection,

assess infection control

practices, and make

recommendations to prevent

ongoing transmission.

Epidemiologic Investigation

The

epidemiologic study

population consisted of all

162 patients who were

receiving hemodialysis at

the unit as of July 1, 2008.

For all patients,

HCV-related test results

reported through the unit's

central electronic

laboratory system and the

NYSDOH Electronic Clinical

Laboratory Reporting System

were reviewed, and patients

were matched against New

York state and New York City

hepatitis surveillance

registries. All current

patients were offered

anti-HCV testing. Because

hemodialysis unit staff

members were not considered

likely sources of HCV

transmission in this

investigation, staff members

were not tested.

Patients

were considered HCV positive

if their serum was 1)

determined positive by

enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

testing with a

signal-to-cutoff ratio

consistent with CDC

recommendations for a

confirmed anti-HCV positive

test or 2) determined

positive by EIA followed by

recombinant immunoblot assay

or nucleic acid testing for

HCV RNA (1).

A chronic case of HCV was

defined as a case in a

patient who was HCV positive

before or upon admission to

the hemodialysis unit. An

incident case was defined as

a case in a patient who was

HCV negative upon admission

to the hemodialysis unit but

who subsequently was

confirmed HCV positive. Unit

medical records for all

HCV-positive patients were

reviewed, and serum from

available patients was

submitted to NYSDOH's

Wadsworth Center laboratory

for HCV sequencing and

phylogenetic analysis.

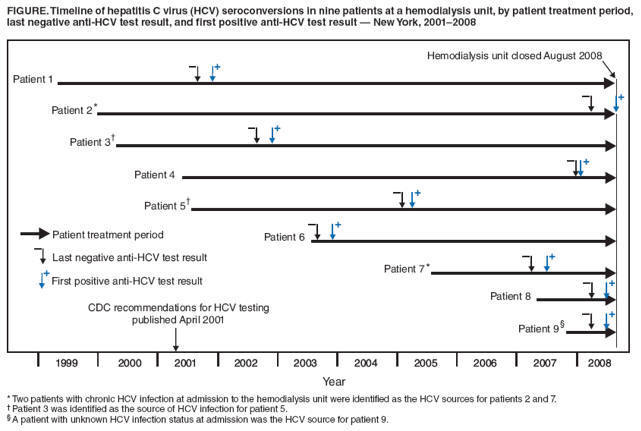

Of the 162

patients, HCV infection

status at hemodialysis unit

admission could be

documented through medical

records and previous test

results for 110 (68%).

Twenty (18%) of the 110 had

chronic HCV infection at

admission. Ninety (82%) were

anti-HCV negative at

admission, of whom nine

(10%) were determined to

have acquired incident HCV

infection, seroconverting to

anti-HCV positive during

2001--2008 (Figure).

Among the

162 patients, a total of 45

(28%) had at least one

anti-HCV positive EIA test

result, either at admission

or during their hemodialysis

treatment period. Serum was

collected and tested from 35

of these patients, of whom

26 had sufficient virus for

sequencing and subtyping of

NS5b region: eight of the

nine patients with incident

infection, 12 patients with

chronic infection upon

admission, and six patients

whose HCV admission status

was unknown. An HCV source

patient was defined as an

HCV-positive patient 1) with

a >95% sequence

identity match in the NS5b

region of the HCV genome

with a patient with incident

infection and 2) who had

received hemodialysis

treatment on recurring days

at the same time as the

patient with incident

infection, during the

seroconverting patient's

exposure period (i.e., from

6 months before the

patient's last negative

anti-HCV test through 2

weeks before the first

positive anti-HCV test). The

joint phylogenetic-epidemiologic

analysis identified four

different patients as the

sources of HCV infection in

four patients who

seroconverted during

2005--2008 (all sequence

identity matches

between source and incident

patients were >98%).

Of the four source patients,

one was among the nine with

incident infection, two were

among those with chronic HCV

infection at admission, and

one had unknown HCV

infection status at

admission. All four patients

with incident infection and

their respective source

patients had dozens of

treatment days in common

(range: 59--121 days). Two

of the four patients with

incident infection had at

least one treatment on the

same dialysis machines as

their HCV source patients;

however, no record existed

of the other two with

incident infection having

been treated during their

incubation periods on the

same machines as their

source patients.

HCV source

patients could not be

determined for five of the

patients with incident

infection because no

sequence identity match was

identified. None of the five

had known HCV risk factors

(e.g., occupational

exposure, injection-drug

use, high-risk sexual

behaviors, or exposure to

known HCV-positive persons).

Two of the five reported no

health-care exposures

outside of the hemodialysis

unit during their exposure

periods; the other three

reported respectively 1) one

emergency department visit,

2) one hospitalization, and

3) one emergency department

visit and two hospital

admissions. Epidemiologic

analysis is continuing in an

effort to define narrower

exposure periods and

determine the mechanism or

mechanisms of HCV

transmission at this

facility.

Site

Investigation

During the

site investigation, NYSDOH

documented inadequate HCV

infection surveillance and

patient follow-up (2).

Numerous deficiencies in

standard infection control

practices also were

identified (2).

The hemodialysis unit did

not obtain confirmatory

testing for anti-HCV

positive results, inform

patients of their change in

HCV infection status, report

HCV seroconversions to the

local health department, or

provide patients with

medical evaluation related

to HCV infection. Contrary

to CDC recommendations (2),

monthly alanine

aminotransferase (ALT)

levels were not obtained

from >90% of HCV-susceptible

patients, and anti-HCV

testing, although conducted

on most patients, was

performed at intervals

ranging from once per month

to once per 2 years rather

than semiannually.

Inadequate

cleaning and disinfection

practices were observed

during site visits in July

and August 2008. A single

bleach-soaked gauze pad was

used to clean a patient's

entire dialysis station,

including dialysis machine

surfaces and ancillary

patient equipment (e.g.,

blood pressure cuff and

shared computer monitor and

keyboard). The bleach

solution was prepared and

stored improperly, and staff

members did not allow

sufficient contact time

between surfaces and bleach.

Visible blood remained on

dialysis chairs, dialysis

machine surfaces, and the

surrounding floor between

patient treatments.

Moreover, direct care staff

members failed to don gloves

with every patient

encounter, change gloves

between patients, or perform

hand hygiene after contact

with patients and soiled

surfaces. Supervisory staff

members failed to address

these breaches. Many of the

direct care staff members

were unaware of the

hemodialysis unit's written

infection control policies,

including those pertaining

to cleaning and

disinfection. Investigators

also noted the lack of a

separate clean area for

medication storage and

preparation and short

turnover periods between

patient treatments.

On August

14, 2008, after evidence of

ongoing infection control

deficiencies and despite

efforts at remediation,

NYSDOH directed the

hemodialysis unit to

transfer all patients

immediately to other

facilities; all patients

were transferred the next

day. The hemodialysis unit

subsequently surrendered its

operating certificate and

paid a $300,000 civil

penalty to the state; the

unit has not reopened. Based

on evidence of HCV

transmission since 2005, all

patients who had received

one or more treatments at

the hemodialysis unit since

January 23, 2004 (the date

of the last facility survey

in which no infection

control deficiencies were

observed) were notified by

mail of the investigation

and advised to be tested for

HCV and other bloodborne

pathogens (i.e., hepatitis B

virus and human

immunodeficiency virus).

Notification letters were

mailed on September 15,

2008, to a total of 657

patients from 37 states and

two territories. As of

January 11, 2009, no

additional HCV

seroconversions had been

reported from health

departments in New York, 13

other states, and one

territory, accounting for

90% of the patients who were

notified.

Reported

by: R Hallack, G

Johnson, MS, E Clement, MSN,

M Parker, PhD, J Schaffzin,

MD, PhD, B Wallace, MD, P

Smith, MD, New York State

Dept of Health; ND Thompson,

PhD, Div of Viral Hepatitis,

National Center for

HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis,

STD, and TB Prevention; PR

Patel, MD, JF Perz, DrPH,

Div of Healthcare Quality

Promotion, National Center

for Preparedness, Detection,

and Control of Infectious

Diseases; J Magri, MD,

Career Development Div,

Office of Workforce and

Career Development; JL

Jaeger, MD, EIS Officer,

CDC.

Editorial

Note:

An estimated

3.2 million persons have

chronic HCV infection, the

most common chronic

bloodborne infection in the

United States (3).

The prevalence of anti-HCV

is estimated at 8% among

chronic hemodialysis

patients (4),

compared with 1.6% in the

U.S. population overall (3).

HCV infection increases the

risk for death among

patients receiving chronic

hemodialysis treatment and

those undergoing renal

transplantation (5).

Many persons infected with

HCV remain asymptomatic,

although progression of

underlying liver disease

occurs in approximately 80%

(6).

Chronic HCV infection is the

leading indication for liver

transplantation in the

United States (7).

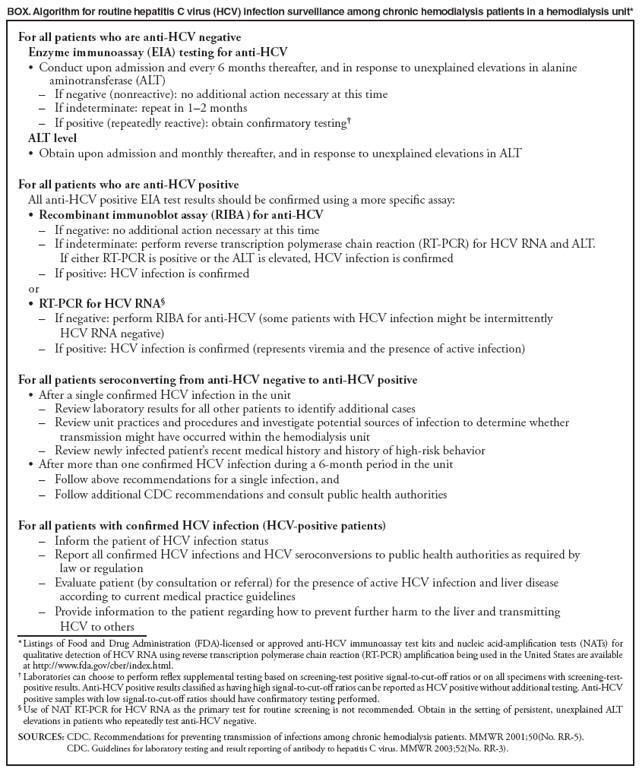

CDC

recommendations for

preventing HCV transmission

in hemodialysis units were

published in 2001 (Box)

(2).

Despite these

recommendations, several

hemodialysis-related HCV

outbreaks have occurred in

recent years; all involved

breaches in infection

control, and most were

identified as a result of

routine HCV screening (8).

CDC recommends initial

anti-HCV screening upon

admission to the unit for

all chronic hemodialysis

patients. For

HCV-susceptible patients,

monthly ALT should be

performed; anti-HCV

screening should be obtained

semiannually thereafter and

in response to unexplained

elevations in ALT, to

facilitate early detection

of transmission and

implementation of control

measures (2).

Routine HCV screening of

hemodialysis patients also

is recommended by the

National Kidney Foundation (9).

However, dialysis providers

are not reimbursed by

Medicare for anti-HCV

screening, and screening is

not required by the Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (10). In the

2008 Medicare conditions for

coverage for end stage renal

disease facilities (10),

CDC recommendations for

preventing transmission of

infections in hemodialysis

units (2)

were incorporated by

reference, with the

exception of screening for

hepatitis C. The referenced

recommendations have the

authority of regulation.

This

investigation documented

four cases of

patient-to-patient

transmission of HCV

infection and identified

five additional patients who

might have acquired HCV

infection while receiving

treatment at the

hemodialysis unit. Multiple

possible mechanisms of HCV

transmission were

identified, including

contaminated health-care

worker hands and treatment

surfaces. Contact

transmission in the setting

of extensive environmental

contamination is a common

mechanism for transmission

of bloodborne pathogens in

hemodialysis units (2).

Because this investigation

was restricted to patients

undergoing treatment as of

July 31, 2008, the actual

number of incident cases at

the hemodialysis unit might

have been larger.

This

outbreak highlights the need

for hemodialysis units to

adhere to recommendations

for infection control and

comprehensive HCV

surveillance, including

routine anti-HCV screening,

confirmatory testing of

anti-HCV seroconversions,

assessment of the adequacy

of infection control

practices in the setting of

documented HCV

seroconversion, and prompt

reporting to the local

health department as

required by reportable

disease laws or regulations.

Had the hemodialysis unit in

this report complied with

these practices, HCV

transmission might have been

identified earlier, and

control measures (e.g.,

reviewing infection control

practices to identify

potential mechanisms of

transmission, ensuring

adherence to unit infection

control policies, and

retraining direct care staff

members) could have been

implemented to interrupt

further HCV transmission.

Because many patients with

HCV infection are

asymptomatic, routine

screening is essential to

detect transmission within

hemodialysis facilities and

ensure that appropriate

precautions are being

followed consistently.

Acknowledgments

This report

is based, in part, on

contributions by E Rocchio,

MA, K Southwick, MD, N

Sureshbabu, and T Kwechin,

New York State Dept of

Health; and K Bornschlegel,

MPH, New York City Dept of

Health and Mental Hygiene.

References

-

CDC. Guidelines for

laboratory testing and

result reporting of

antibody to hepatitis C

virus. MMWR 2003;52(No.

RR-3).

-

CDC. Recommendations for

preventing transmission

of infections among

chronic hemodialysis

patients. MMWR

2001;50(No. RR-5).

-

Armstrong GL, Wasley A,

Simard EP, McQuillan GM,

Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ.

The prevalence of

hepatitis C virus

infection in the United

States, 1999 through

2002. Ann Intern Med

2006;144:705--14.

-

Finelli

L, Miller JT, Tokars JI,

Alter MJ, Arduino MJ.

National surveillance of

dialysis-associated

diseases in the United

States, 2002. Seminars

in Dialysis

2005;18:52--61.

-

Kamar N,

Ribes D, Izopet J,

Rostaing L. Treatment of

hepatitis C virus

infection (HCV) after

renal transplantation:

implications for

HCV-positive dialysis

patients awaiting a

kidney transplant.

Transplantation

2006;82:853--6.

-

CDC. Surveillance for

acute viral

hepatitis---United

States, 2006. MMWR

2008;57(No. SS-2).

-

Sharara

AI, Hunt CM, Hamilton

JD. Hepatitis C. Ann

Intern Med

1996;125:658--68.

-

Thompson

ND, Perz JF, Moorman AC,

Holmberg SD. Nonhospital

health care--associated

hepatitis B and C virus

transmission: United

States, 1998--2008. Ann

Intern Med

2009;150:33--9.

-

Gordon

CE, Balk EM, Becker BN,

et al. KDOQI US

commentary on the KDIGO

clinical practice

guideline for the

prevention, diagnosis,

evaluation, and

treatment of hepatitis C

in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis

2008;52:811--25.

-

Centers

for Medicare and

Medicaid Services,

Center for Medicaid and

State Operations/Survey

and Certification Group.

End Stage Renal Disease

(ESRD) Program:

interpretive guidance

version 1.1. Baltimore,

MD: Centers for Medicare

and Medicaid Services;

2008. Available at

http://www.cms.hhs.gov/eog/downloads/eo%200526.pdf.

Figure

Return to

top.

Box

Return to

top.

Use of

trade names and

commercial sources

is for

identification only

and does not imply

endorsement by the

U.S. Department of

Health and Human

Services.

References to

non-CDC sites on the

Internet are

provided as a

service to MMWR

readers and do not

constitute or imply

endorsement of these

organizations or

their programs by

CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health

and Human Services.

CDC is not

responsible for the

content of pages

found at these

sites. URL addresses

listed in MMWR

were current as of

the date of

publication.

|

All MMWR

HTML versions of articles

are electronic conversions

from typeset documents. This

conversion might result in

character translation or

format errors in the HTML

version. Users are referred

to the electronic PDF

version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR

paper copy for printable

versions of official text,

figures, and tables. An

original paper copy of this

issue can be obtained from

the Superintendent of

Documents, U.S. Government

Printing Office (GPO),

Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800.

Contact GPO for current

prices.

**Questions or messages

regarding errors in

formatting should be

addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.

Date last reviewed: 3/5/2009

td>

|