|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Ask the Mayo Clinic:

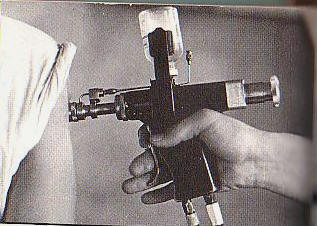

Whatever happened to 'jet injectors?' Published 10:00 pm, Sunday, December 7, 2008 Read more: http://www.seattlepi.com/lifestyle/health/article/Ask-the-Mayo-Clinic-Whatever-happened-to-jet-1293851.php#ixzz2N6VZHEbn Dear Mayo Clinic: I remember we used to get vaccines and other shots using an air gun, and lots of people could get shots quickly. I haven't seen this done for a long time. Why? Were problems discovered with that method? It seems that it would be an efficient way to give flu shots, for instance, in a really short time. A: Using an air gun -- also called a jet injector -- is a fast way to deliver vaccines. But jet injectors were discontinued for mass vaccinations about five years ago because of possible health risks. A jet injector uses high pressure to force a vaccine or other medication through a person's skin. Their speed made jet injectors very efficient, so many people could be vaccinated quickly. They were often used in the military. Although they weren't pain-free, jet injectors didn't involve needles. The result was less discomfort than a needle injection, and they caused less anxiety in people who were afraid of needles. In some cases, however, jet injectors could bring blood or other body fluids to the surface of the skin while the vaccine was being administered. Those fluids could contaminate the injector, creating the possibility that viruses could be transmitted to another person being vaccinated with the same device. Of particular concern were viruses transmitted by blood, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and hepatitis C. HIV can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) -- a chronic, life-threatening condition caused by damage to the immune system. Hepatitis can cause chronic inflammation of the liver and lead to serious liver damage. Greater awareness of these diseases and other blood-borne illnesses led to increased scrutiny of ways they might be spread. Although no widespread outbreaks of these diseases were caused by jet injectors, the risk of blood and body fluid contamination of the equipment made jet injectors no longer acceptable for vaccinations. Instead, most vaccines now are administered by needle injection, typically in the arm for adults and in the thigh for children. In the case of the flu vaccine, another option that became available about three years ago is a nasal mist. All it takes is one spray in each nostril. It's easy, quick and painless. No needles are involved. This method has limitations, though. The nasal spray vaccine contains a low dose of weakened live virus. If a person's immune system is severely suppressed due to illness or medical treatment, the live virus could, theoretically, cause the flu in that person. Also, the flu vaccine nasal spray appears to be less effective than needle injection (flu shot) in people 50 and older. For these reasons, the nasal spray is only approved for healthy people ages 2 to 49. The flu shot is approved for people 6 months and older. Because the viruses in the flu shot aren't live, it can't cause you to get the flu but it will enable your body to develop the antibodies necessary to ward off influenza viruses. Mayo Clinic recommends that everyone get the flu vaccine. Although people tend to think of influenza as a minor illness, it can cause pneumonia and lead to hospitalization, particularly in high-risk groups. At particularly high risk for influenza are all children 6 months to 18 years and everyone older than 50. Others at increased risk of flu-related complications are pregnant women, people who have a chronic medical condition such as heart disease, diabetes or asthma, and anybody whose immune system is compromised. Unfortunately, about 36,000 Americans die each year as a result of influenza. So, it's important to get a flu vaccine every year to protect yourself. The current methods of delivering the vaccine are safe and effective and, although they aren't as fast as the jet injectors, getting a flu vaccine doesn't take much time. Flu season lasts from fall through early spring. The earliest Mayo Clinic usually sees a flu outbreak is September or October. But about 60 percent of influenza outbreaks in the U.S. occur after January. Contrary to popular belief, even if you don't get your flu vaccine by the end of November, it's not too late. The majority of outbreaks occur after that time, and you can still receive the vaccine as late as March or April. -- Gregory Poland, M.D., Vaccine Research Group, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Read more: http://www.seattlepi.com/lifestyle/health/article/Ask-the-Mayo-Clinic-Whatever-happened-to-jet-1293851.php#ixzz2N6VRHwYA |

|